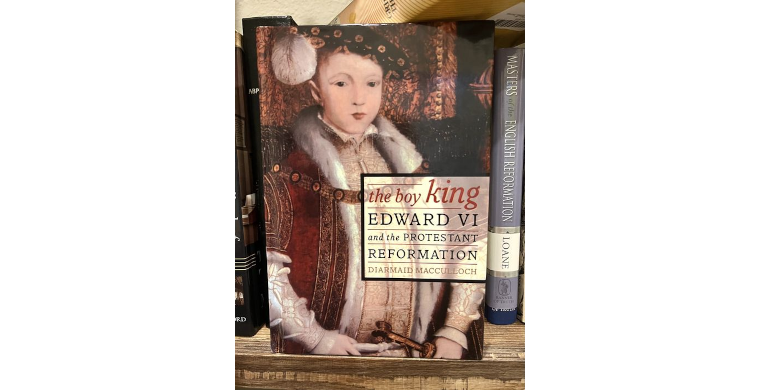

Edward VI, "Boy King" Led English Reformation

By Chuck Collins

www.virtueonline.org

July 8, 2024

Edward VI died July 6, 1553 at the young age of 15.

He reigned only six short years as King of England and Ireland: the "Boy King." As the long-awaited male heir of Henry VIII (and Jane Seymour), Edward was England's first Protestant king who, with the full support of the leaders around him, began the cataclysmic theological eruption that we know today as the English Reformation.

Under Edward, the Church of England was firmly planted in the theology of the Continental Reformation. The Reformation in England had its own characteristics and nuances, of course, but in all essential theological matters it was the same 16th century Reformation experienced wherever the Bible was read seriously as the impulse to reforming the church - in Germany, Switzerland, and other parts of Europe.

Historian Diarmaid MacCulloch asserts that in Edward's thirteenth year the boy-king began to actually lead the nation, especially in the realm of religion - so much so, he contends, that the Church of England can fairly be called "Edward's church."

Nevertheless, the story of his reign is also the history of the two protectors who ostensibly ruled England in his name: Edward Seymour (Duke of Somerset 1547-1549) and John Dudley (Duke of Northumberland 1449 to the king's death). John Foxe labeled Somerset "the good duke" for the ways he supposedly promoted the Protestant agenda, but there is also plenty of evidence that he was a pretty self-serving politician.

"Somerset uneasily combined the reforming zeal of Thomas Cromwell, the chutzpah of Cardinal Wolsey and the flashy populism of Queen Elizabeth's doomed earl of Essex" (MacCulloch). Northumberland was a quieter, steadier presence as Lord President of the Council who had been a convinced Protestant for many years. But his was "idealism without fireworks" (MacCulloch). Both protectors, Seymour and Dudley, aimed to destroy an apostate church and build another.

The chief architect of the theology and worship of the Church of England was Thomas Cranmer, Edward's Archbishop of Canterbury. With the full support of the King and his protectors, Cranmer wrote the confession for the English church (The Articles of Religion), edited and contributed to the first book of Homilies (sermons to be read sequentially in all churches), and he penned the famous Book of Common Prayer.

These are recognized today as the Anglican formularies that provide the backbone of what Anglicans around the world believe. Upon Edward's untimely death, his stepsister Queen Mary Tudor (Bloody Mary), was unsuccessful in stopping the Protestant train. The trajectory of Edward's Church would see its "settlement" in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I who grounded Anglican identity once-and-for-all in the authority of Holy Scripture as upheld, explained and preserved in Anglican's historic formularies.

MacCulloch memorably points out that the changes brought on by Edward VI were seen in three new pieces of furniture that were added to churches in Edwardian England: a wooden table, a poor box, and a pulpit.

Moveable wooden tables replaced stone altars across the kingdom as a visual reminder to everyone that the Medieval sacrifice of the mass was no longer the religion of the land. It was replaced by a whole new understanding of "real presence" in Holy Communion that honors the central teaching of Holy Scripture: salvation by grace through faith alone. Cranmer taught, and it was written into the Anglican formularies, that Christ is spiritually present in the eucharist, not in the bread and wine such that we would worship him there, lift him up, and gaze upon him, but rather in the hearts and affections of those who receive the grace of the sacrament by faith.

A poor box to collect alms was ordered to be placed in every church. This served as a continual reminder that the people's offerings were not to support the pope or a wealthy and corrupt clerical class, or to furnish ornate churches, but for the primary mission of the church: to help the lost and the least for the sake of Christ.

And pulpits became front and center in church architecture to reinforce the clear message that God is heard most directly when the Bible is taught and heard, with all other "authorities" ceding to the primary authority of God's inspired Word.

MacCulloch wrote that "the pulpit would remain the central visual emphasis of most English parish churches down to the nineteenth century, when the Oxford Movement, in a remarkably successful piece of theological alchemy, restored the primacy of the altar."

Dean Chuck Collins is a Reformed theologian. He resides with his wife and family in Houston, Texas