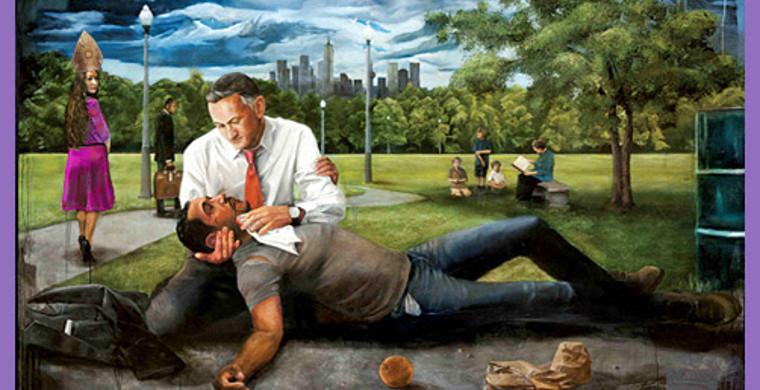

"I need a friendly bishop," said the child abuse survivor, as the prelate passed by on the other side

By Martin Sewell

Archbishop Cranmer Blog

http://archbishopcranmer.com/

Oct. 22, 2017

Two years ago, Archbishop John Sentamu gave one of those sermons which you know you will remember.

It was delivered in York Minster to the assembled Houses of the General Synod of the Church of England, and Archbishop John was plainly on 'home turf'. He was preaching on the Good Samaritan, and we had an icon to contemplate as he took us slowly and in-depth through the familiar text.

Plainly he knows the acoustics of the Cathedral well and used them to good effect, repeatedly returning to the same refrain at points in the story and demanding of his listeners: "Who will help? You? You? You?", leaving the words to echo around and find their mark.

The church took the lesson to heart and has enthusiastically raised the question with the government when discussing refugees, foodbanks and the implementation of Universal Credit.

But what about matters closer to home? How about those who have suffered abuse within the church?

The story of the Good Samaritan challenges us to measure up to that standard.

When I attended the protest of victims at Canterbury, I met some survivors whose stories I did not know, so I agreed to listen and learn, and after a brief exchange of emails we agreed to talk later on the telephone.

The day before that call, I was contacted by a survivor who was in serious need, but was seeing no progress on the case settlement despite there being little doubt on liability. More worryingly, the survivor's circumstances were worsening and homelessness was feared. There is more to the case but I must respect confidentiality.

An advance of something between 5% and 10% of the value of the claim would fix the problem and release the survivor from prolonged anxiety and frustration, so I urged that an advance payment on the settlement be sought.

We have been told in recent weeks that the church is more responsive to survivors, so it seemed to me to be an eminently reasonable request. It is not unusual in litigation where liability is not in issue.

The survivor was understandably reluctant to 'beg' for anything, and was anxious not to be seen as motivated by money. I therefore suggested that I could make a low-key suggestion that an advance payment might be considered, and this was agreed.

In his letter to Gilo, Archbishop Justin had written: "There are lessons to learn and I am keen that we learn them and make any changes necessary." And it seemed to me that making a swift response to an emergency might be a part of the reformation in culture that we sorely need in this area. 'By their fruits ye shall know them..' came to mind.

The following day the church gave the survivor two responses: one that help should be sought from "a sympathetic bank manager"; the other that the claim had to go through "the usual channels" (ie slowly). "I don't need a friendly bank manager," said the survivor sadly, "I need a friendly bishop."

Terse, dismissive, unfeeling... the Church of England could have been responding to a bothersome jobsworth at any secular organisation.

I am a naive fellow. I thought the church in its brave new world of sensitivity to the needs of child abuse victims might have a mechanism for swift executive action to help in circumstances such as this. I thought we might be geared to take risks for the gospel, confident that even if the House of Bishops had to report occasionally, after decades of making mistakes protecting abusers, they had unfortunately 'wasted money' by being over generous to victims, that the General Synod might have given them a sympathetic pass. Some of us might even have offered them a round of applause, given the history, congratulating them for daring to be fools for Christ.

It is actually not unprecedented for the church to facilitate a payment to a victim 'off the balance sheet'.

In the case of Bishop George Bell, I had been puzzled at an early stage why the church insurers had not taken the legal point that the claim was statute barred, and wondered what their legal view was on the case, generally. My General Synod colleague David Lamming had pursued the point and ascertained the slightly surprising fact that, in the Bell case, the payment had come not from our insurers but had been privately brokered, half from the Church Commissioners and half from a private individual.

So it appears that the Church of England can be financially resourceful and creative during its preparation to throw one of its dead saints under a bus to improve its image, but when a living victim of child abuse needs urgent help, we apparently have no mechanism for responding.

The following day another survivor and I were having a conversation, and in passing he emphasised (like the earlier victim) that money was a secondary consideration. In fact, he said casually that some don't need compensation because they come from very wealthy families.

Being utterly shameless and opportunist, and knowing how God moves in mysterious ways, I asked if I could be incredibly cheeky and enquired if anyone he knew might help a survivor in need. I was asked how much was needed. I gave an indication. "Leave it with me," he said.

The money was in the needy bank account within a few hours -- plus 50 per cent.

Who will help? You? You? You?

"Find a sympathetic bank manager," said the CofE priest.

"The usual channels," said the Levite.

"Brother, sister, let me serve you," said the outsider, who had been paying attention.

This is a guest post by Martin Sewell who is a retired Child Protection Lawyer