Silent Anglicans

Why evangelicals in the Church of England need to talk openly

By Peter Sanlon

https://www.e-n.org.uk/

August 27, 2018

One year before WWI broke out, Winston Churchill wrote a memo: 'Timetable of a Nightmare.'

It predicted details of the coming war. Churchill frequently warned of the danger his country faced -- the majority of his fellow leaders merely complained about him. Sir Henry Jackson spoke for many when he wrote that he 'did not like the style' of Churchill's writing. Churchill's warnings of danger were ignored and instead his manner, style and motivations were impugned. Trying to prepare the military and nation to defend itself felt like wading through treacle with chains of iron around his neck -- because free and open debate about the actual issues was precluded by those in a position to act.

Crisis on the horizon

A similar problem weighs upon evangelicals in the CofE today. Crisis looms on the horizon, but leaders, organisations and churches are frightened even to debate the issues impartially. Over the past year I have been asked by three of the well-known evangelical parachurch organisations if I would speak in a debate about the spiritual state of the CofE? In all three cases the debates were called off because none of those evangelicals who privately defend the CofE were willing to have their arguments examined in public. Evangelicals are a constituency reputed to be courageous, idiosyncratic and counter-cultural. Why then are evangelicals in the CofE so frightened to debate the deep problems we face in our denomination? There are a number of reasons:

Outsiders?

1. Admitting that the problems in the CofE are severe would force ministers to lead ministries outside the established church. Those less than a decade off retirement lack the energy, and those in their 20s cannot see how they could raise the necessary finances to replicate CofE provision. In many parts of the country a CofE minister's remuneration package (including rent) is about £65,000. Stepping away from that calls for considerable faith.

Ignore the denomination

2. Many evangelicals in the CofE believe they can ignore the denomination. There are strengths and weaknesses of every polity -- but one creates an intractable problem when evangelicals in any system claim they can reject the principles of their own polity. One CofE minister intimated to me that it mattered not a jot what his bishop believed about anything. Deep inconsistencies have to be embraced in order to hold such views alongside being a minister in the CofE. Open discussion of the heresy that has captured the denomination would expose these.

Social class

3. We have a problem with class. This is why Acts 29 are organising a conference on the topic. In the CofE, a group of ministers who hail from upper-middle-class backgrounds shape the national agenda for our constituency. Several of them are good friends. Still, it is without a doubt the case that their cultural background makes them frightened of open public debate about theological issues. In a widely circulated paper on the problem of class, the late Mike Ovey wrote: 'I am disturbed that we spend so little time on what is blindingly obvious to outsiders, that so much of our implicit leadership has an upper-crust profile. This implicit leadership structure creates a real dilemma. If we appoint a bishop from this implicit leadership, then questions arise about transparency, fairness and whether the individual has the requisite qualities. If we do not, how will a new bishop exercise oversight over a member of this implicit leadership?' Mike Ovey went on to explain how our captivation to upper-class leadership ties us into a toxic secretive form of decision making -- the very kind exposed by open debate.

Big churches dominate

4. Conservatives in the CofE find that our leadership structures are dominated by our larger churches. These churches are able to negotiate deals with the denomination small churches cannot. They can do so due to financial clout and size -- but as they focus energies on those negotiations they ignore the opportunity to rally and support others effectively. Peter Jensen describes this as the 'Fortress Church' strategy. It feels safe inside a fortress -- but one needs to remember that a besieged fortress falls eventually.

Being groomed?

5. It puzzled me for a while why a couple of well-known conservative leaders mimic the establishment propaganda that evangelicals can flourish alongside liberals. It made sense when I heard that one of them had been invited to speak at Lambeth Palace and the other has for some years been on the bishops' training programme. Evangelicals often feel excluded -- being promised a position of influence as a bishop is seductive. The price of being groomed is that one must not bite the handler, so debate becomes toothless.

Separation from false teaching

6. We conservative Anglicans have been notoriously poor at applying the Bible to our culture. We have focused on helping people become Christians -- applications beyond that have been lacking. Evaluating the CofE takes us beyond our exegetical comfort zone -- we are called to ask what it really means for us to separate from false teachers. We are ill-prepared for such debates.

Parachurch

7. All the parachurch organisations that represent conservatives in the CofE now commend some form of tolerating the CofE's heresies. CEEC hopes for a solution from the Archbishop himself. Reform has morphed into Church Society, which is careful to challenge the CofE in terms no stronger than any CofE bishop would voice. Renew gestures to AMiE as a network free of the CofE -- but the vast bulk of its energy is focused on helping people do ministry within the CofE. Where would people go to debate the issues and formulate an effective way forward? The answer from all organisations is that we should quietly wait and see what happens.

Conflicting strategies

8. It is said that people in our constituency will all do different things. Leaving aside the fact that no army has won a war by adopting conflicting strategies, this has given rise to a false view of unity. That idea is that unity will be preserved by not evaluating the theological foundations of our differing approaches. Failure to debate openly fosters false unity and means that factors other than truth shape actions.

As one minister criticising Church Society's approach wrote: 'I'm deeply unconvinced by what seems to be the current pressure to hold our tongues because everyone is in a different situation, so we will follow different strategies. I don't think we strive to maintain our unity by not speaking especially in a context where we feel dangerous steps are being taken.' I realise that in summarising these concerns I will likely be accused of undermining unity. I urge those who would lay that charge to seek the deeper unity which lies the other side of honest debate. There are numbers of positive steps that could be taken -- but they can only be explored with those willing to discuss the nature of the problem faced.

Consequences

A tragic consequence of failure to debate the issues facing us is that we are less well prepared for future events than we could be. Discussing the issues and past decisions would be painful for all -- we would all need to admit our past failures of leadership. It would be worthwhile, as it would leave us better prepared for what is coming.

Another consequence of our failure to talk openly is that we are formed into the image of the CofE. Our denomination has been captured by a spirit that says truth and error can be held together; that institutional positions and money matter more than Jesus' words. The longer we refuse to debate the relevant issues the more deeply we will be formed into the likeness of an institution God has abandoned.

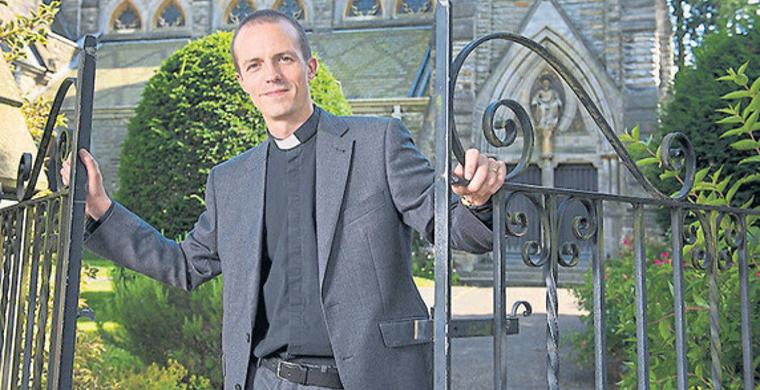

Peter Sanlon is Vicar of St Mark's Church, Tunbridge Wells and Director of Training, the Free Church of England