Should we stop referring to God as 'he'?

By Ian Paul

PSEPHIZO

https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/should-we-stop-referring-to-god-as-he/

Sept. 18, 2018

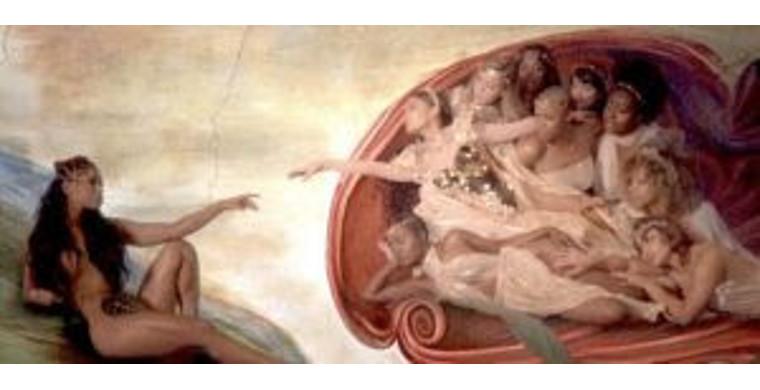

Last week the polling company YouGov published the results of a survey asking Christians what they thought about God's gender. Their 'shocking' discovery is that very few agree with Ariana Grande's claim in her latest single:

With Ariana Grande's recent single being entitled "God is a Woman" a new YouGov survey reveals that British Christians aren't so sure about that: in fact, just 1% believe that God is female.

There are some basic problems with the report of the poll itself--the main one being that YouGov don't give any clear indication as to their sample methodology and what they mean by 'Christian' when they claim 'Christians believe that...' Are these people who are self identifying? Were they sampling outside churches on a Sunday? Did they ask any questions about actual practice and attendance? Without this information, the 'Christian' claim is fairly meaningless.

Despite the YouGov headline, Premier correctly reported the less exciting but more accurate observation that 'Most British Christians believe God does not have a human gender identity'. But Olivia Rudgard of the Telegraph has managed to make more of a story from the survey, by getting comment from Rachel Treweek, the Bishop of Gloucester:

The Church of England should avoid only calling God "he", a bishop has said, as a survey found that young Christians think God is male. The Rt Revd Rachel Treweek, bishop of Gloucester, the Church of England's first female diocesan bishop, said: "I don't want young girls or young boys to hear us constantly refer to God as he," adding that it was important to be "mindful of our language".

She raised concerns that non-Christians could feel alienated from the Church if its public pronouncements used solely male language to describe God.

"For me particularly in a bigger context, in all things, whether it's that you go to a website and you see pictures of all white people, or whether you go to a website and see the use of 'he' when we could use 'god', all of those things are giving subconscious messages to people, so I am very hot about saying can we always look at what we are communicating," she said.

It is worth observing the progress of language here, as a sobering lesson on what happens in the publicity process. First, the survey finds that most 'Christians' don't believe God is gendered. Then 'nearly half' believe God is male; then 'young Christians think...'; and finally 'The Church should not use male language'. In subsequent (copy-cat) pieces, Rachel Treweek goes from being the first female diocesan to the first female bishop, and this is now a 'growing problem'--so who knows what the story would look like with a few more repeats. And apparently this is a problem of perception in mission and evangelism (without any evidence cited) so we have moved rather a long way from the original survey.

________________________________________

The reason why Olivia Rudgard went to Rachel Treweek with this survey is because it is a reply of comments that she made in 2015, when there was again quite a lot of coverage. But then and now, the headline-grabbing stories collapse a series of separate though related questions about God and gender:

1. Does Scripture claim God is male?

2. Are there both male and female metaphors for God?

3. Are we at liberty to change them?

4. Should we use feminine pronouns for God?

5. Is this a missional issue as claimed?

As I have noted previously in this discussion, the most prominent images in Scripture of God are the male images, but the female images are not absent. There is quite a good list of them here; the main references are Hosea 11.3--4 and 13.8, Isaiah 42.14, 49.15 and 66.13, Deut 32.11-12 and 18. Perhaps the most striking ones in the NT are of the kingdom of God being like a women kneading dough (Lk. 13:20-21), God being like a woman who has lost a coin (Luke 15.8--10) and Jesus likening himself to a mother hen (Matt 23.37, Luke 13.34). Most striking of all as a female image in ministry is Paul's description of himself as a women in labour (Gal 4.19).

Underlying this is a very clear claim: God does not have a gender. Although the gendered identity of humanity has its origins in our creation in the image of God, Gen 1 is very clear that neither gender on its own is the image of God:

So God created human beings in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. (Gen 1.27)

In a culture and context where gods where male or female, and where for the most part the male gods conquered and controlled the female, this is a striking statement. If we think that the male more truly represents the 'image and likeness' of God than the female, we are contradicting a central claim of the biblical revelation about God.

This connects with other central claims about the nature of God. In the discussion with the woman at the well in John 4, Jesus states that 'God is spirit' and, despite debates in Judaism about whether God has a body (following from OT language about the arms, hand, eyes and even nostrils of God), Christian theology has consistently believed that (in the words of Article I of the XXXIX) God is 'without parts or passions'. Gender (or, more accurately, 'sex') is a bodily reality; we are sexed as male and female because we have male or female bodies, and if God is not bodily then God cannot be sexed.

________________________________________

If, according to Scripture, God is not male, the question then follows as to why most of the images of God are male in Scripture, and whether these are a reflection of the culture of the time so that they might be open to renegotiation.

New Testament scholar Jon Parker observes something significant about male language in the cultural context of the biblical writings:

To me, the use of masculine language in the ancient world has less to do with "patriarchy" than it does the presumption of the gendered nature of fruitfulness. The masculine was the first stage of progeny. There were (and are) plenty of things to celebrate about the feminine in Scripture. For example, when it comes to long-suffering toil, the exclusively feminine experience of bearing and birthing is almost always reached for, cf. Num 11:12; John 16:2-21; Gal 4:19.

By contrast, the masculine "sowed the seed." Of course, we now know that men and women contributed equal DNA, but they didn't. In ancient observation of the world: seed + soil/womb = life. Of course, too, this is metaphorical when speaking of God. But when thinking about the One who created/sourced all things, it was, I think very hard for any ancient Mediterranean person (Greek or Jewish; male or female) to think about that being as feminine. It wouldn't make sense. That this sense of the first stage of progeny was then used by many to wrongly (and unbiblically) promote men over women is beside the point in why the language was used, I think.

To reflect God's nature as "unsourced source" is still a good reason to use the masculine about God, despite abusive patriarchy spoiling that language (which of course cannot be ignored as we try to speak about God today).

But, as Alastair Roberts points out, the differences between male and female--and particularly between the meaning of 'mother' and 'father'--and not only contextual, but relate to a fundamental asymmetry in the way that the two function in parenting.

The Scriptures use feminine imagery and metaphors of God, but it primarily identifies God using masculine pronouns, names, and imagery. Male and female imagery isn't interchangeable.

The fact that God is called 'Father' can't be substituted by 'Mother' without changing meaning, nor can it be gender neutralized to 'Parent' without loss of meaning. Fathers and mothers are not interchangeable, but relate to their offspring in different ways. A mother's relationship with her child is a more immediate, naturally given union of shared bodies. It is more clearly characterized by close empathetic identification. A father's relationship with his child, by contrast, is characterized by a 'material hiatus' and more typically involves a greater degree of 'standing over against' the child. While motherhood is more naturally given and more rooted in the body through the process of gestation and nursing, fatherhood is established principally by covenant commitment. If he is to be more than a mere inseminator, a man must lovingly commit himself to his wife and offspring. The different nature of the father's relationship with his child also means that he more readily represents law and authority to the child: he can stand over against the child to a degree that the child's mother can't.

All of this matters when we are speaking about God. A shift beyond biblical feminine metaphors and imagery to feminine identification of God will have a noticeable effect upon our vision of God, our ideas of where God stands in relation to us, the way that we conceive of the Creator-creature distinction, and the sort of language that we use when speaking about sin, separation from God, etc.

Let's recover the feminine imagery of Scripture, but let's do so in a careful and theologically principled way, rather than presuming that any symbol or language we choose to employ for God is as appropriate as any other.

Given that the ecumenically agreed Apostle's Creed declares faith in 'God, the Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth' and in 'Jesus Christ, God's only Son', and given that the Lord's Prayer addresses God as 'Our Father', then to start changing this language touches on central issues of confessional faith, rooted in the consistent testimony of Scripture. I confess I have never been a fan of the New Zealand Prayer Book re-write of the Lord's Prayer, even though it has been widely used:

Eternal Spirit,

Earth-maker, Pain-bearer, Life-giver,

Source of all that is and that shall be,

Father and Mother of us all,

Loving God, in whom is heaven...

Is it possible or helpful to use feminine pronouns when referring to God? It is worth noting that Rachel Treweek (and Jo Bailey Wells, also quoted in the Telegraph article) do not advocate this; if God is not gendered/sexed, then their suggestion is to avoid using pronouns at all. But this is extremely difficult in ordinary speech, and the biblical texts don't appear to have any qualms about it. The problem that we have in English (and in many languages) is the lack of a UGASP--an UnGender Assigned Singular Pronoun (in French it is common to use on which is such a pronoun). In other words, it is very difficult to refer to an individual without specifying his or her (there, you see?) sex. If we call God 'Father' and Jesus 'Son', it would be nonsense not to use a masculine pronoun. Some claim that the Hebrew for 'Spirit' (ruach) is feminine, which gives us a precedent for using a feminine pronoun (as, curiously enough) I experience from the person leading worship yesterday. But it is well established that grammatical case does not indicate personal gender; in any case ruach is occasionally masculine (Ps 51.12 and elsewhere); in the NT the Greek term pneuma is neutral; and in fact use of a feminine pronoun draws attention to the question of gender, and if anything suggests that God is indeed gendered, rather than suggesting that God is beyond gender.

________________________________________

Finally, it is worth reflecting on whether this is indeed a pressing pastoral or missional issue. Kate Wharton offers customary insight and common sense in the earlier discussion:

We need to make use of the very helpful feminine/maternal imagery we find in Scripture, perhaps most of all in pastoral situations where someone struggles for whatever reason with the masculine imagery. Having said that, I have never been in a pastoral situation where someone has struggled with calling God 'Father' and ended up instead calling God 'Mother' -- rather they have worked through what the issue is for them, what that means for their relationship with their earthly father, and how they can most helpfully know and relate to God as Father, understanding him to be the perfect example of fathering.

And, going back to the YouGov survey, it is striking that more women than men think of God as male, which doesn't appear to have stopped them coming to faith and coming to church. One of the challenges to this claim about mission is the still high proportion of women in churches which not only lean towards the masculine images of God, but believe that ministry and leadership should be primarily male.

________________________________________

And does it really help the cause of women in leadership in the Church to continue to be connected with this debate? One of my friends on Facebook has hosted some fairly unpleasant comments in reaction to a perception that this issue is about rejecting biblical language and biblical ideas about the nature of God--even though a careful reading of the comments made in the newspaper article doesn't actually say that. But given that this doesn't appear to be a serious missional issue, is it time to move on to other things?