J. I. Packer on Revaluing the Book of Common Prayer

By Sinetortus

https://anglicanway.org/

November 22, 2020

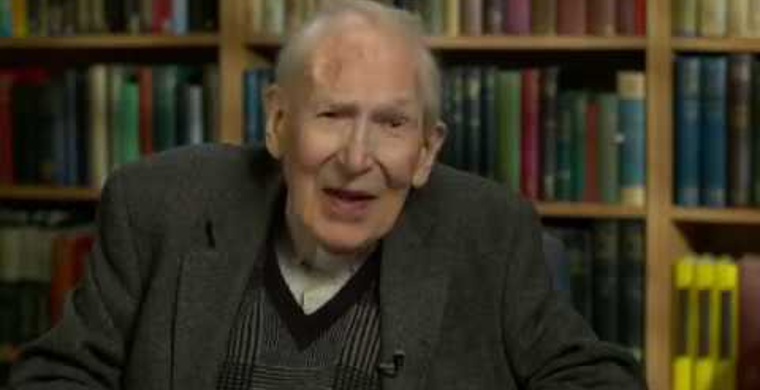

As we recall the great work and achievements of the late Professor J I Packer (image above from Regents College, Canada) who died in July this year, it is apposite to recall from the Society's archives this article first published in 2000:

For Truth, Unity, and Hope: Revaluing the Book of Common Prayer

(Comprising part of a very slightly edited version of an address first given to the Canadian Prayer Book Society

It references the Canadian BCP of 1962 as well as the Book of Alternative Services or BAS, of which it offers an illuminating critique)

By The Revd. Professor J.I. Packer

Everything that was written in the past was written to teach us so that through endurance and the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope. May the God who gives endurance and encouragement give you a spirit of unity and encouragement among yourselves as you follow Christ Jesus, so that with one heart and mouth you may glorify the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ(Romans 15:4-6).

Teaching, uniting, and encouraging Christian people are three specific purposes of God, whereby his plan of salvation is carried forward in our lives...

I am sure it will do us good to remind ourselves how fruitfully the Prayer Book fulfills this threefold divine agenda.

The first of God's goals that Paul mentioned was teaching, the building up of the mind. The Prayer Book teaches: and what its main services mainly teach is, precisely, the gospel of Christ. The structure of those services expresses the gospel, just as their words and phrases do, and the power of Anglican liturgy to instil the gospel into human hearts has been central to Anglican experience for nearly 450 years. This is the legacy to us of that still unappreciated genius, Thomas Cranmer, the mid-sixteenth century reforming Arch- bishop of Canterbury. Let me show you what Cranmer did.

Cranmer saw that the way to make liturgy express the gospel is by use of a sequence of three themes. Theme one is the personal acknowledgment of sin; theme two is the applicatory announcement of God's mercy to sinners; theme three is the response of faith to the grace that is being offered. The sequence is evangelical and edifying -- edifying, indeed, just because it is evangelical. Gospel truth is what builds us up!

See this sin-grace-faith sequence in Cranmer's Bible services, Morning and Evening Prayer.

First we are summoned to confess our sins, and we do so. Next we hear the good news that God pardons and absolves all who truly repent and unfeignedly believe his holy gospel. Then the rest of the service is the third step in the sequence, the expressing of responsive faith. We say the Lord's Prayer, with special emphasis on "forgive us our trespasses". We sing canticles of praise for salvation, starting in the morning with "O come, let us sing unto the Lord: let us heartily rejoice in the strength of our salvation", and in the evening with "My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour". We hear the word of God with the purpose of leaming more about his mercy and the way in which we saved sinners are to serve him in this world. We pray for others in the confidence that the God who has blessed us will bless them too. All this is faith's response to the knowledge of God's saving grace in and through our Lord Jesus Christ. The sequence is profoundly simple, profoundly biblical, profoundly moving, and profoundly enriching to the soul.

The Holy Communion service is basically structured by the use of the same sequence.

The Ante-Communion (collect for purity and law of God, pointing to sin; prayer for mercy after the law and New Testament readings, pointing to grace; confessing the Creed, hearing the sermon, and praying for the world as expressions of responsive faith) takes us through the sequence in an introductory way, and this is followed by a second journey through it in poignant applicatory terms. "Ye that do truly and earnestly repent you of your sins, and are in love and charity with your neighbours, and intend to lead the new life, following the commandments of God and walking from henceforth in his holy ways: Draw near with faith, and take this holy Sacrament to your comfort." Yes, but the first step towards the Table must be confession of "our manifold sins and wickedness which we, from time to time, most grievously have committed". Then the second step is the Absolution, backed by the scriptural assurances of mercy for sinners through Christ which we call the comfortable words. And the third step is thanks- giving for salvation, faith responding to grace, which is what the Sursum Corda ("Lift up your hearts") is all about.

Then, after all this, we come to the sacrament that confirms the word of grace by setting before us in visible symbol Christ's "full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world". When we receive the elements, the words of administration express application: we are told to consume them in remembrance of Calvary, be thankful, and feed on Christ in our hearts. It is clear that our receiving and consuming is meant to express responsive faith: Lord Jesus (our hearts should be saying), as I take this bread and wine so I receive you afresh to be the bread of my life, the life of my soul, my Saviour and my God. This is magnificent, surely.

The Book of Alternative Services (or BAS of 1985) is less forthright in words, and less clear in structure, about these things; if we value the gospel-oriented liturgy that Cranmer bequeathed to us (1962 Canadian version is based on 1662 is almost all Cranmer, though a few changes were made), we shall see the BAS as retrograde on what is central, a step backwards rather than forwards, a cheap modem runabout offered in exchange for a classic liturgical Rolls-Royce, and we shall certainly think it a pity.

The second of God's goals that Paul mentioned was uniting, the extending and deepening of fellowship. Part of our Anglican heritage is a centuries-old experience of the unitive power of all joining together in the same worship and leaming together to enter into it and make it our own. This too is part of Cranmer's legacy: his strategy was to abolish local liturgies, of which England had a number, and to prescribe just one, in order to bring about national unity in gospel faith and gospel worship. I want to celebrate the wisdom of this strategy which, until quite recently, was a mark of Anglicanism throughout the world.

(And, quite specifically, I wish to put it to you that it is retrograde when modem revised forms in Canada, in England, in the USA and elsewhere include at key points, most notably the Prayer of Consecration in the Holy Communion service, half a dozen alternative forms between which the celebrant may take his choice. With such variety we cannot achieve the degree of unity and togetherness among church people that comes when we are all leaming to worship God with a single liturgical form.)

Of course, to fulfil this unitive role, the liturgical form used has to be a good one! It has to express the biblical and evangelical truth to which the Church is corporately committed, and it must do this in a full and faithful way; also, it must express the concerns about spiritual life and honouring God that Church members do or should have. I believe that on all that is central and crucial and foundational our 1962 Prayer Book actually does this, and does it superbly. To be sure, it uses a style of speech that is based on the English Bible as this emerged in the 90 years between Tyndale and the King James Version, and it is semi-technical in its use of key biblical concepts, and hence it is true and indeed important to say that using the Prayer Book properly involves leaming a language. But should this daunt us?

We do not complain of having to leam the language of computers, daisy wheels and bytes and floppies and so on; we simply learn it, in order to be able to use computers; why then should anyone balk at learning the language one needs in order to worship God? There are technical terms in the Bible, which those who want to know about God labour to learn; why should we expect things to be I know, of course, and so do you, that for half a century people have been assuring us that up-to-date worship forms can be devised that will express everything Cranmer ex- pressed while using only everyday words -- the language of secular life, that is -- so that the meaning of the liturgy becomes clear to the most casual worshippers, without their having to leam any-thing. But the idea is unrealistic; it is a mere will-o'-the-wisp; the thing cannot be done. Try to do it, as the BAS seems to try, and what happens is that the truth-content of worship gets watered down, so that liturgical expression becomes vague, and less worthy worship is thus made inevitable. It is no wonder many Anglicans are moved to say of our Canadian venture into this area, what a pity, and even, what a disgrace. It is no wonder, either, that the BAS divides rather than unites.

Ever since the sixteenth century, worshippers have been finding that the forms of words in our Prayer Book are wonderfully enriching and enlarging to the soul. They mesh in beautifully with the teaching of Holy Scripture, which they echo, and the experience of literally millions of Anglicans has been that the more light one gains from the Bible the more wisdom one finds in the Prayer Book. If we taught the Prayer Book to our congregations, as our Anglican forebears used to do (this, I believe, is where today's Anglicans have missed out), and if we showed the links between Prayer Book and the Bible at each point, and if we explained that Christian worship is a leamed activity and helped people to leam it, I believe we should find the Prayer Book exerting its unitive power once more in a way that would amaze us. May God give us who teach the good sense to tackle this task as a step towards recovering the intemal unity that God intends for our Anglican Church.

The last of God's goals that Paul mentioned was encouraging. Encouraging is a matter of imparting hope and strength, by making Christians aware of their resources in God: thus encouraged. Christians will live courageously and consistently for God, however much the culture is against them and however often they find themselves swimming against the stream. One thing I love about our Prayer Book is that it makes so much of the greatness of God's gracious power to strengthen us in our spiritual weakness; this is encouragement that I need. Spiritually weak? -- well, yes, I certainly am, and so I believe are you; threats to our faith, our moral and spiritual integrity, and our zeal for God's cause, are constantly with us; spiritually speaking, in these days of dramatic spiritual decline, we are beset by what the Prayer Book calls "many and great dangers", however materially secure we may seem to be. I am thankful that the Prayer Book offers me so many prayers pointing to the great grace and power of my great God and Saviour to strengthen his people when they are under great pressure.

Here, for instance, is the collect for Trinity IX:

Grant to us. Lord, we beseech thee, the spirit to think and do always such things as be rightful; that we, who cannot do anything that is good without thee, may by thee be enabled to live according to thy will.

Here is Trinity XIX:

O God, forasmuch as without thee we are not able to please thee: Mercifully grant, that thy Holy Spirit may in all things direct and rule our hearts.

You see the emphasis: we are weak and impotent; God is great and strong; urgently, therefore, we cry for his help. Surely this is realistic; surely this is the biblical way to pray. The alternative collects that we are offered today are often more eloquent, in their smooth, bland way, but are invariably less urgent. The sense that we are praying out of a realization of our weakness, sinfulness, and spiritual danger, and out of experiences of being harassed, distracted, and discouraged, is much diminished. The BAS, one might say, is for nice people whereas the Prayer Book is for real people. I do not find that the BAS helps me to pray as much as the Prayer Book does, nor does it encourage me in the same way.

Do we sufficiently appreciate our Prayer Book?

We need to revalue our Prayer Book upward: that, I believe, would be the best and most direct route to the renewal in our Church of the blessing for which Paul prayed -- that the God who gives endurance and encouragement may give us a spirit of unity among ourselves as we follow Christ Jesus, so that with one heart and mouth we may glorify the Father, and that the God of hope may fill us with all joy and peace as we trust in him, so that we may overflow with hope by the power of the Holy Spirit. God grant it! Amen

(Originally published in the January-February 2000edition of the precursor magazine of the Anglican Waythen known as Mandate)

J.I. Packer was an Oxford graduate where he also wrote his D.Phil. dissertation under Geoffrey Nuttall on the soteriology of the Puritan theologian Richard Baxter. He was ordained in the Church of England as a deacon in 1952 and priest in 1953

In 1955, he moved to Bristol where he taught at Tyndale Hall till 1961 during which he wrote an article in the Evangelical Quarterly denouncing the Keswick theology then popular among evangelicals as Pelagian. He also published his first book, Fundamentalism and the Word of God while based there in 1958. He returned to Oxford in 1961, where he served first as librarian and then warden of Latimer House (which he founded with John Stott) until 1969. He next became principal of Tyndale Hall, Bristol, and from 1971 until 1979 he was associate principal of the newly formed Trinity College, Bristol, which had been formed from the amalgamation of Tyndale Hall with Clifton College and Dalton House-St Michael's.

He became editor of the Evangelical Quarterly and it was from material in a series of articles he published there that he derived the text of his book Knowing God which sold over 1.5 million copies. In 1977, he signed the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.

In 1979 he moved to Regent College in Vancouver, where in 1989 he was named the first Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology, which title he held until he was named a Regent College Board of Governors' Professor of Theology in 1996.

Among his publications were:

Knowing God, Fundamentalism and the Word of God, Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God, Growing in Christ, God has Spoken, Knowing Man, Beyond the Battle for the Bible, God's Words, Keep in Step with the Spirit, Christianity the True Humanism, Your Father Loves You, Hot Tub Religion, A Quest for Godliness, Rediscovering Holiness, Concise Theology, A Passion For Faithfulness, and Knowing Christianity.