AN EXPERIENTIAL ANGLE ON DIVINE PREDESTINATION

By Roger Salter

Special to Virtueonline

www.virtueonline.org

October 20, 2021

Anglican soteriology, the doctrine of salvation, is based on the exquisite doctrine of electing love as summarized in Article 17 of our Reformational Confession of Faith. With theological accuracy, Scriptural terminology, and enormous charm, God's eternal love for his chosen ones is spelt out with sagacious balance and proportionality of emphasis. Our redemption as sinners is all of grace. It is wrought entirely by God in Christ alone, received through divine effectual calling alone, manifested by faith and holy living before God through the enabling of the great Three-in-One, all in due time. Looking to Christ alone with sincere desire is the way open to all for assurance of salvation.

"Christ . . . is the mirror, in which it behoves us to contemplate our election". Inst. 111: xxiv.5.

"It behoves all believers to be assured of their election, that they may learn to behold it in Christ as in a mirror. Tracts 111:155 - Jean Calvin

None who wait upon the Lord will be disappointed. We acknowledge God's sovereignty and trust the gospel. There is no real need for endless head-scratching or undue angst, for God's unconditional promise in Christ is sure. Election is our comfort accessed through our steady gaze at the crucified One. No one reading Article 17 should be discouraged; a statement which beautifully combines the truth of predestinating grace with belief of the gospel.

In this way the theological knot is untied. All who call upon the Lord shall be saved. Predestination is God's inalienable prerogative. We salute his blessed foreordination. Humble response to the gospel is his command and our responsibility. Effectual calling wrought in us is a most pleasurable consolation. God deals with his administration of special grace. We make our invited plea to him. That constraint is a first conscious intimation of the work of grace. Desire for God and his salvation is the initial inkling of his favor. Fervent desire is full possession.

"He is enthroned in heaven, but prayer will bring him down to the heart . . . and if we feel one desire towards him, we may accept it as a token that he gave it us to encourage us to ask for more" JOHN NEWTON, letter, August 24, 1774.

Effectual calling is the least "speculative" element, so say, to our comprehension of the grand and edifying doctrine of predestination. It yields a most satisfying taste of the loving-kindness of the Lord: "As the godly consideration of Predestination, and our Election in Christ, is full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort to godly persons, and such as feel in themselves the working of the Spirit of Christ, mortifying the works of the flesh, and their earthly members, and drawing up their mind to high and heavenly things, as well as because it doth greatly establish and confirm their faith of eternal Salvation to be enjoyed through Christ, as because it doth fervently kindle their love towards God:" Article 17.

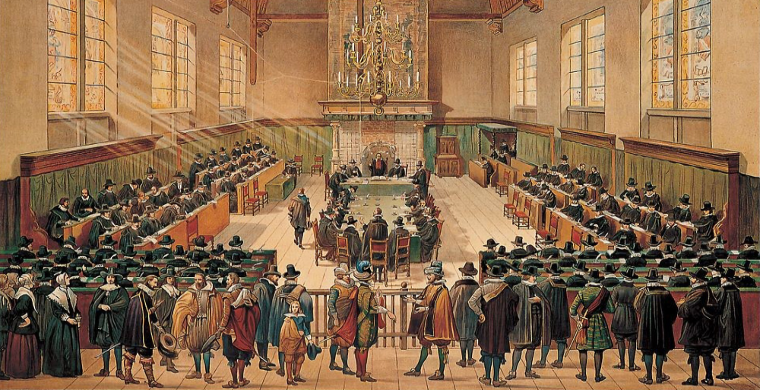

The elements of the TULIP formulation - the summary of the Canons of Dort, deemed consonant with the Anglican Articles by the several Church of England delegates attending the Synod of Dort (1618-19), can be affirmed logically, even by the unconverted mind, but only the new birth can cause that frisson of delight in grasping the Lord Jesus who has already taken us into his firm grip (John 6: 28-30). Effectual calling is the alluring voice of the Shepherd bidding his flock to himself (John 10. 3-4, 16: 15-16).

Predestination is a biblical fact: "It is of grace that any are saved; and in the distribution of that grace he does what he will with his own, -- a right which most are ready enough to claim in their own concerns, though they are so unwilling to allow it to the Lord of all", Letter March 24, 1774. "It is our part to be abased before him, and quietly hope and wait for his salvation in the use of his appointed means", Letter 1, November11, 1775. JOHN NEWTON

It is quite proper in our discourse on God to pronounce his sovereignty and to acknowledge his decree(s). We need to stand in awe of him and to fear him both as his creatures and as repugnant sinners of rebellious will and deviant, lawless ways. The divine dominion over all things, even eternal destinies, stimulates the human mind to reverence God, honor his power, and to urgently seek his undeserved favor. The truth of effectual calling translates a subject that could easily become a matter of abstract contemplation and speculation (merely a theological conundrum to turn over, even indifferently (philosophically) in the mind) - into a felt attraction and affection toward an intensely loving God, who seeks out his own from all those bent on defying him until the bitter end of a hateful existence of relentless antipathy. All are bidden to bathe in this love, but only those whose hostility to God is broken are graciously compelled by intense and persistent wooing to yield to the triumph of grace.

"But suppose there should be one of God's chosen who become so bad that there is no hope for him? He never attends a place of worship; never listens to the gospel; the voice of the preacher never reaches him; he has grown hardened in his sin, like steel that has been seven times hardened in the fire; what then?" That man shall be arrested by God's grace, and that obdurate, hard-hearted one shall be made to see the mercy of God; the tears shall stream down his cheeks, and he shall be made willing to receive Jesus as his Saviour. I think that, as God could bend my will and bring me to Christ, He can bring anybody.

Why was I made to hear his voice,

'Twas the same love that spread the feast,

And enter while there's room;

That sweetly forced me in;

When thousands make a wretched choice,

Else I had still refused to taste,

And rather starve than come?

And perished in my sin.

Yes, "sweetly forced me in;" -- there is no other word that can so accurately describe my case.

CHARLES SPURGEON

Old Testament scholar Norman H Snaith addresses the issue of the "overplus" of saving love, whereby, given his general love for mankind, God in certain cases (electing love) performs in some persons "more than is required". In other words, there is, with the reality of distinguishing grace at least, a definite divine predilection in motion.

"Even though man himself will not turn to God, yet God himself can bring this to pass. God's sure unswerving love will find a way by which even stubborn, unrepentant Israel can turn. It will mean new hearts, but God will accomplish even this. . . Herein are the beginnings of those doctrines of the Christian Faith which we sons of the Reformation know assuredly to be at the root of the Gospel, in chief, Salvation by Faith alone, and through grace, for even the first stirrings towards repentance in the human heart are the work of God himself. Page 122.

In times of utter failure, he gave them new hearts and put a right spirit within them, taking away their fleshly, stony hearts. For the love of God which chose them in the first instance is also the love by which God himself enables them to fulfill the conditions by which alone that love can be come effective in them . . . this is achieved by that new heart and spirit which God himself implants in Israel's heart, and by that new strength which God himself alone can give. Page 142.

Again, it is true the prophets assume that a man may change his way of life if he will. But they realize that man does not so will. They never anticipated that more than a very small remnant would ever turn back to God. This is clear in Isaiah 1:9, 7:3, and especially Ezekiel 5: 1-4, where the prophet expects the salvation of only a few of a third part. Men are fast bound by their deeds, so that they cannot turn, Hosea 11; 7. Surely this is the very antithesis of Pelagianism. It equals anything in Augustine. If ever there is to be any turning, then God himself must turn them. Page 66. The Distinctive Ideas of the Old Testament, Epworth, 1955.

Prosper of Aquitaine (c390-c463) was a loyal disciple of Augustine in his theology of grace, and as a pious laymen commended it widely among believers and bishops, and even to Pope Celestine Ist. Eventually Prosper somewhat modified his predestinarian stance by affirming that God willed the salvation of all men through the gift of general grace sufficient to leave men without excuse. However, his Augustinianism was loyally retained in his tender opus, The Call of the Nations, in which his argument for effectual calling was posited as particular to the elect. In this doctrine, this blessed interior event of effectual calling - Prosper's coaxing of all to participate in salvation - distinguishing and sovereign grace is maintained. The grace that actually reaches and touches the human heart melts its resistance and obduracy.

Martin Luther's subscription to the fact of predestination is clear in his writings and teaching, and is clearly overt in his denial of free will towards the matter of salvation in the natural and unregenerate man (The Bondage of the Will, Commentary on Romans). But it is observed that the logical basis for election in Luther's thought has an anthropological basis in the helplessness of man and the effectual result of grace at work in the human heart. In organizing Luther's theology of predestination, it does not rise from the notion of sovereignty assigned to God as a matter of divine decree or prerogative but more so to the plight of sinful, spiritually impotent human nature. Luther the pastor is innocent of even Augustinian construction of Scriptural logic. He urges Christ as Deliverer rather than the determiner of destiny. He is very much the man of the effectual call, and the sympathetic encourager of the perplexed with regard to salvation.

Herman Bavinck (The Doctrine of God) speaks of "the anthropological and soteriological basis of Luther's doctrine of predestination" page 353, and William Hastie endorses that sentiment in referring to the dominance of Luther's "subjective faith" and its grounding in the principle of Justification by Faith (an accurate principle) but distinct from the more solid and substantial Reformed principle established in its "cardinal doctrine of free sovereign grace, [which] so far from being antiquated, is the rational and necessary culmination of all other truth yet known to us about religion" (Theology Of The Reformed Church, page 22).

As a Reformed Church the Archbishops of Canterbury, after the Elizabethan Settlement (1559), from Archbishop Matthew Parker (1559-1575) through Edmund Grindal (1575-1583), John Whitgift (1583-1604) Richard Bancroft (1604-1610), and George Abbot (1611-1633) were all uniformly of Calvinist conviction until the appointment of the notorious William Laud, opponent of Reformation doctrine with the support of Charles Stuart.

It is sometimes alleged that Bancroft was an exception and odd man out, but this is to confuse his dislike of the Puritans (most provocative in his time) with his adherence to the faith of Augustine. Bancroft in 1598 cordially licensed and encouraged the publication of a Calvinist treatise that asserted the doctrine of unconditional election. Bancroft, approving the doctrine of predestination, considered ASCENDENDO not DESCENDENDO - he reasoned from effectual calling not from a sought certitude of a favorable divine decree. Calvin warned against such personal probing into the matter of one's election. Bancroft affirmed, "I live in obedience to God in love with neighbor, I follow my occasion therefore I trust God has elected me and predestined me to salvation not thus, which is the usual course of argument: God has predestined and chosen me to life, though I sin ever so grievously, yet I shall not be damned, for whom he once loveth, he loveth to the end" (Augustus Toplady, page 236). Bancroft recognizes the grace of predilection but notes the fruits of the grace of disposition. Prevenient grace is his refuge.

This a very different view to that of John Wesley concerning prevenient grace. Wesley contended that through prevenient grace every sinner was brought to a state of equipoise before God with the capacity to choose salvation or the option to refuse it. This must inevitably mean that the selection of grace is due to a superior moral or spiritual quality in the one who makes a positive decision, and there is then a human contribution to our salvation, but "who makes you different from anyone else? What do you have that you did not receive? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as though you did not? (1 Corinthians 5:7). (One has actually and stunningly heard the spoken celebration of the anniversary of one person's willingness to give God permission to save their soul!).

Generally speaking, human nature recoils from the notion of divine election and Arminianism is the religious result of the natural human philosophy that in everything man must be in control, the divine will be deferring to the volition of man. Man must permit the divine will to prevail given man's unquestioned captaincy of his soul. The word of God pronouncedly counters this blasphemous assertiveness. The Lord is totally sovereign and man is utterly dependent on God's superior determinations. They are inevitably wise and just and effectively carried through in the accounts of his love in salvation.

"There is an exclusiveness in God's love. This idea of exclusiveness has been part of 'the offence of the gospel' since almost the first days. Such an idea must necessarily be involved in some degree as soon as the word 'choose' is used. We may not like this word 'choose' or its companion 'election'. They may be abhorrent to us, but they are firmly embedded in both the Old and New Testaments. Either we must accept this idea of choice on the part of God with its necessary accompaniment of exclusiveness or we have to build a doctrine of the Love of God other than that which is Biblical. The alternative is clear, and we do not see how it can be avoided. It may be that we cannot answer the questions which are involved in it, but the teaching is there plainly enough. Why is it, for instance, that this one is chosen, and not that one? (Snaith, page 139).

Many subscribers to the doctrine of election call a halt at this juncture, not daring to enunciate a view on preterition, such as Snaith himself, the major Swiss Reformer, Johann Bullinger (later moving closer to Calvin) and the English Puritan bishop, John Hooper. The absolute sovereignty of grace was upheld, but there was caution on the matter of "the passing by" of the non-elect. This hesitancy existed largely from a pastoral motive, consistent with the exhortation summed up in the Anglican Article 17: "But for inquisitive and unspiritual persons who lack the Spirit of Christ to have the sentence of God's predestination continually before their eyes is a dangerous snare which the devil uses to drive them either into desperation or in to recklessly immoral living (a state no less perilous than desperation). Furthermore, we need to receive God's promises in the manner in which they are generally set out to us in Holy Scripture, and in our actions, we need to follow that will of God which is clearly declared to us in the Word of God." Bold Luther himself came to adopt a similar outlook in his dealing with sensitive consciences, and the badly distorted view of election had its influence on the dissolute life of Lord Byron and the mental health of the frantic mother of Bertrand Russell. Oddly, the author of the novel Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe, was warned concerning his overt sense of being among the elect.

Given that the Lord is not under strict obligation to rescue any lost sinner - we admit that fact when we cry for mercy - there is sometimes a callous and unfeeling presentation of predestination lacking in pastoral astuteness. There is an extensive treatment of this issue in an article by the undoubted doughty exponent of unconditional election, Robert L. Dabney, entitled God's Indiscriminate Proposals Of Mercy, Discussions Evangelical and Theological, Vol 1, Banner of Truth, 1967.

For the sake of brevity Dabney's thirty-one-page essay will not be summarized as to its close Scriptural and theological detail, and only a portion of his final paragraph will be quoted as to the disposition of God toward all men in general. His conclusion is not posited at this stage as a final verdict on the matter but as an invitation to ponder a difficult matter for so many minds.

"The solution, then, must be in this direction, that the words, 'so loved the world,' were not designed to mean the gracious decree of election, though other scriptures abundantly teach there is such a decree, but a propulsion of benevolence not matured into a volition to redeem, of which Christ's mission is a sincere manifestation to all sinners. But our Saviour adverts to the implication which is maintained even in the very statement of this delightful truth, that those who will not believe will perish notwithstanding. He foresees the cavil: 'if so, this mission will be as much a curse as a blessing; how is it, then, a manifestation of infinite pity?' And the remaining verses give the solution of that cavil. It is not the tendency or primary design of that mission to curse, but to bless; not to condemn but to save. When it becomes the occasion, not cause, of deeper condemnation to some, it is only because these (verse 19) voluntarily pervert, against themselves, and acting (verse 20) from a wicked motive, the beneficent provision. God has a permissive decree to allow some thus to wrest the gospel provision. But inasmuch as this result is of their own free and wicked choice, it does not contravene the blessed truth that Christ's mission is in its own nature only beneficent, and a true disclosure of God's benevolence to every sinner on earth to whom it is published. [This view seems to harmonize with the teaching of both Gerrit Berkouwer and Geoffrey Bromiley in their treatment of Predestination].

Given the severity of the view of Dutch theologian Herman Hoeksema, denying even common grace, it is useful to weigh the conversations of highly competent Reformed theologians, such as G.C. Berkouwer (Divine Election) and Geoffrey W. Bromiley (The True Image). Charles Spurgeon opined that God would issue the divine sentence of final banishment with a regretful eye.

There is much spiritual advantage in approaching (and proving) divine election from the consideration of effectual calling - effectual grace. It brings to bear the tender love of Christ in an active way upon the consciousness of the believer. He powerfully draws his loved ones to that blessed posture of the apostle John when he reclined affectionately upon the Savior's breast. Jesus reveals his beauty and every aspect of his excellence, irresistibly attracting us to himself as the sweetness of the honeycomb ineluctably attracts the bee. Herein is the delicious reality of the mystical union with Christ made known to the people of God - the witness of the Spirit of Christ to the child of God. Nothing surpasses the sweet communion with the Lord. All that the Father gives me will come to me, and whoever comes to me I will never drive away (John 6:37 - permanent bonding). Behold I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him, and he with me (Revelation 3:20 - continued refreshment of relationship; elder brother's company).

Rudyard Kipling must have had at least a scintilla of good regard toward Calvin as witnessed in his poem M'Andrew's Hymn, 1893: A portion follows, though no doubt the remainder is actually a comic, perhaps slightly ribald spoof of Presbyterian morality entertained by a seasoned shipmate from Scotland:

Lord, Thou hast made this world below the shadow of a dream,

An', taught by time, I tak' it so -- exceptin' always Steam.

From coupler-flange to spindle-guide I see Thy Hand, O God --

Predestination in the stride o' yon connectin' rod.

John Calvin night ha' forged the same-- enormous, certain, slow --

Ay, wrought it in the furnace-flame -- my "Institutitio".

Mechanical construction fascinated McAndrew as a ship's engineer.

Thomas Cranmer was the master architect of Anglicanism, the principal craftsman of its Ceremony (liturgy) and Confession (learning from Scripture). In terms of theological category among the many options within Christendom the Archbishop was staunchly Augustinian, a colleague of the church father universally recognized as the eloquent Doctor of Grace.

Dairmaid MacCulloch observes of Cranmer, "His theology was structured by predestination, a theological concept which Anglicanism has on the whole decided to treat with caution" (All Things Made New, Oxford, 2016, page 276).

May it not be suspected that the flaccid and confused state of Anglican doctrinal conviction may be due to the to the good ship Ecclesia Anglicana jettisoning its captain's precious cargo of sovereign grace. Maybe the crumbling of Anglicanism's once solid and stately edifice is attributable to the poor maintenance of its Cranmerian structure. The ship under Admiral Welby is a sinking wreck. The building supervised by re-designer Cottrell is being demolished beyond recognition and usefulness.

In his biography of Cranmer MacCulloch writes:

The mature Cranmer was a predestinarian; he had left behind the freewill theology of Erasmus, which once he had admired. This should not in itself surprise us. Any theologian who reads Augustine or begins meditating on the theme of the grace and majesty in God is liable to be driven to the logic of the doctrine in considering the scheme of salvation: theologians on both sides of the Reformation gulf which opened up in sixteenth-century Western Christianity acknowledged God's overarching control of human destiny, Ignatius Loyala as much as John Calvin. Within the developing Protestant tradition to which Cranmer was now contributing, predestination was a necessary corollary of the thinking of Martin Luther on grace and faith, and it was already one of the root assumptions of the main reformers of central Europe (especially Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr) before Calvin assumed his dominant role among the Swiss" (Thomas Cranmer, page 211).

It is interesting to note that the most fervent advocates of predestination, along with Calvin, namely Peter Martyr and Martin Bucer, were among the most intimate and beloved colleagues of the archbishop who invited these men to professorships at Oxford and Cambridge respectively. Their individual conversations with Cranmer must have been warm and many. At one time in its history at least, the primatial abode at Lambeth registered the voices of orthodoxy.

However, MacCulloch goes on to remark, "From the seventeenth century, majority opinion in the Church of England echoed the distaste for Calvin and all his works which is first prominent in one of England's greatest theologians, Richard Hooker, so this essential fact about the author of the Prayer Book was thrust into obscurity "(op cit).

This comment needs a little clarification. Until the appointment of Archbishop William Laud Calvinism was clearly the dominant theology of the Church of England and bishops such as John Davenant and Joseph Hall, among others remained loyal to the thought of Augustine and the Reformation. Moreover, Richard Hooker upheld the Calvinist tradition on predestination, though more moderately perhaps. "Already in 1586 he emphasized that election involved absolutely nothing predisposing God to favor the elect, 'no more than the clay when the potter appoints it to be framed for an honorable use, nay not so much, for the matter whereupon the craftsman works he chooses, being moved with the fitness which is in it to serve his turn: in us no such thing.' Summarizing his position on predestination in terms similar to the Lambeth articles, Hooker asserted:

That God has predestined certain men, not all men. 2. That the cause moving him hereunto was not the foresight of any virtue in us at all. 3. That to him the number of his elect is definitely known. 4. That it cannot be but their sins must condemn them to whom the purpose of his saving mercy doth not extend. 5. That to God's foreknown elect, the final continuance is given. 6. That inward grace whereby to be saved, is deservedly not given unto all men. 7. That no man comes to Christ whom God by inward grace of his Spirit draws not. 8. And that it is not in every, no not in any man's own mere ability, freedom and power to be saved, no man's salvation being possible without grace. Daniel F. Eppley, The Reformation Theologians, Edited by Carter Lindberg, Blackwell Publishers, 2002.

As a part of the Church of God may Anglicanism once again rejoice to align itself with the solid and sound truth of the Word of God that informs and adorns the marvelous confession of the electing love of God as the foundation of our Gospel tradition.

Predestination to life is the eternal purpose of God, whereby (before the foundations of the world were laid) he has consistently decreed by his counsel which is hidden from us to deliver from curse and damnation those whom he has chosen in Christ out of mankind and to bring them through Christ to eternal salvation as vessels made for honor. Hence those granted such an excellent benefit by God are called according to God's purpose by his Spirit working at the appropriate time. By grace they obey the calling; they are freely justified, are made sons of God by adoption, are made like the image of his only begotten Son Jesus Christ, they walk faithfully in good works and at last by God's mercy attain eternal happineARTICLE 17

Of Predestination and Election.

Predestination to Life is the everlasting purpose of God, whereby (before the foundations of the world were laid) he hath constantly decreed by his counsel secret to us, to deliver from curse and damnation those whom he hath chosen in Christ out of mankind, and to bring them by Christ to everlasting salvation, as vessels made to honour. Wherefore, they which be endued with so excellent a benefit of God, be called according to God's purpose by his Spirit working in due season: they through Grace obey the calling: they be justified freely: they be made sons of God by adoption: they be made like the image of his only-begotten Son Jesus Christ: they walk religiously in good works, and at length, by God's mercy, they attain to everlasting felicity.

As the godly consideration of Predestination, and our Election in Christ, is full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort to godly persons, and such as feel in themselves the working of the Spirit of Christ, mortifying the works of the flesh, and their earthly members, and drawing up their mind to high and heavenly things, as well because it doth greatly establish and confirm their faith of eternal Salvation to be enjoyed through Christ as because it doth fervently kindle their love towards God: So, for curious and carnal persons, lacking the Spirit of Christ, to have continually before their eyes the sentence of God's Predestination, is a most dangerous downfall, whereby the Devil doth thrust them either into desperation, or into wretchlessness of most unclean living, no less perilous than desperation.

Furthermore, we must receive God's promises in such wise, as they be generally set forth to us in Holy Scripture: and, in our doings, that Will of God is to be followed, which we have expressly declared unto us in the Word of God.

The Rev. Roger Salter is an ordained Church of England minister where he had parishes in the dioceses of Bristol and Portsmouth before coming to Birmingham, Alabama to serve as Rector of St. Matthew's Anglican Church