415 YEARS AGO, ANGLICANISM WAS BORN IN AMERICA

By Chuck Collins

https://www.facebook.com/chuck.collins.sa

June 16, 2022

June 16, 1607 is the birthday of Anglicanism in America. On this day Captain John Smith and 104 others celebrated the Lord's Supper when they arrived safely in Jamestown, Virginia. Jamestown was the first permanent English colony in America, settled some thirteen years before the pilgrims landed in Plymouth. Anglicans were America's original forefathers!

The expression of faith they brought with them was that of the 16th century Protestant Reformation. How do we know this? William Strachey, secretary of the colony in 1610, wrote a first-hand account of their first simple church building - the same chapel in which John Rolfe and the Indian princess Pocahontas, were famously married in 1614 - "In the midst [of the fort] ... is a pretty chapel...it is length threescore foot, in breadth twenty-four...and a communion table of black walnut..."

Since Thomas Cranmer's 1552 Book of Common Prayer until the 1979 Prayer Book revision, the communion table was called a "table" so that is wasn't confused with an "altar" and the medieval Catholic understanding of the sacrament.

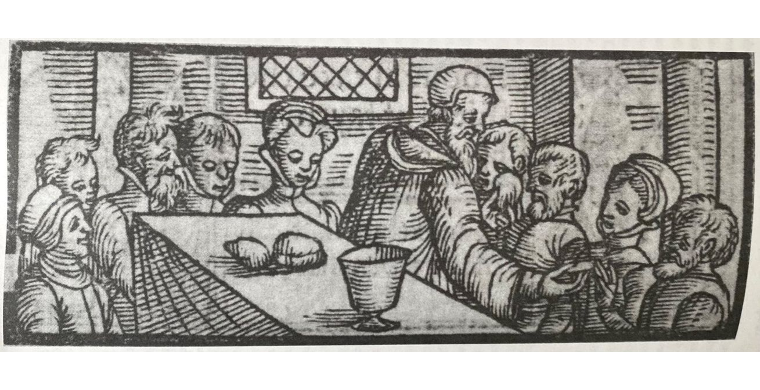

On an altar a sacrificing priest re-offers Jesus as a sacrifice. The Church of England was clear that Jesus was sacrificed once and for all on the cross (Heb 10:10) and that the Holy Communion service is not a re-sacrifice. As the Anglican formularies state, the Church of England understood that Christ is really present in the eucharist, not corporeally in the bread and wine as Catholics (and Lutherans) believe, but spiritually present in the hearts and affections of those who receive the grace of the sacrament by faith. "By faith" is the key to understanding the Reformation, and this is the central teaching behind Anglican sacramental understanding and worship.

The English reformers were clear that stone altars permanently fixed to the east end of churches were idolatrous. Standing at them with their backs to the congregation were sacerdotal priests saying and doing private things in a foreign language, all pointing to the moment of consecration at which bells were rung and Jesus was lifted up for all to gaze upon.

The Bishop of London, Nicholas Ridley, stressed the need to wean people from "the popish" idea of sacrifice at the communion table where we do not come to "sacrifice up Christ again" but rather "we come to feed upon him, spiritually to eat his body and spiritually to drink his blood." The 1552 Prayer Book added a new communion rubric that states that the "table. . .shall stande in the body of the churche, or in the chauncell," with the priest positioned "at the north syde."

The original practice of the Church of England was to have a moveable wooden communion table positioning lengthwise in the chancel, with the minister presiding at its north end. When the Jamestown chronicler described "a communion table of black walnut," he was making a theological statement about their reformational understanding of Holy Communion.

This remained the practice until the Laudian reforms (Archbishop William Laud) in the 1630s when tables were fastened again to east walls of churches, altar rails were constructed around them to spotlight where the magic takes place, chalices were reintroduced replacing "cups," and the practice of bowing to altars upon entering a church or one's pew was introduced. The Roman term "mass" for Holy Communion was discontinued altogether after the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, never to be used again in the English church, except by 19th century revisionists who secretly wished they were "Catholics without the pope."

"Table" remained "table" until the 1979 Prayer Book revision when it was rendered "altar" for the first time, along with the introduction of the fraction and fraction anthem (the breaking of the bread in a separate, dramatic action after the words of institution, announced by: "Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us"). This shows the creeping influence of the 19th century Oxford Movement that sought to reintroduce into this church some pre-Reformation understandings and ideals.

Now we see why Gerald Bray begins his book on Anglicanism claiming that "Anglicanism as we think of it today is essentially a nineteenth-century invention" (Anglicanism: A Reformed Catholic Tradition). Article 31 of the Thirty-nine Articles specifically calls the sacrifices of the mass "blasphemous fables and dangerous deceits."

END