Archbishop Justin Welby's Amritsar apology was aimed at appeasing British Hindus

EXCLUSIVE

By Jules Gomes

www.julesgomes.com

September 23, 2019

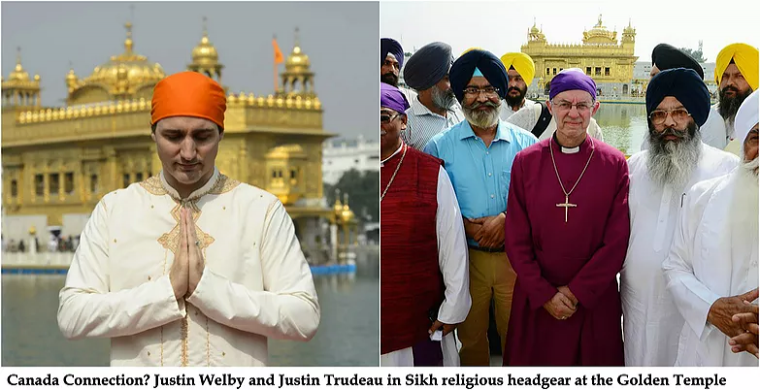

The Archbishop of Canterbury's prostration at Amritsar was intended to appease a powerful British Hindu lobby who wrote to Lambeth Palace demanding an apology and calling General Dyer, responsible for the massacre, "a white supremacist and devout Anglican," interfaith sources have disclosed.

The letter from the Global Hindu Federation (GHF) quoted Anglican repentance for "the Church's colonialist 'methodology'" issued by Canadian Anglican archbishops Michael Peers in 1993, followed by Fred Hiltz in 2008 and July 2019 and called on Archbishop Welby to apologise for "the suffering inflicted upon Hindus, Sikhs and other peoples of India."

In his letter of 15 August, the anniversary of India's independence, Pandit Satish K. Sharma, GHF president, stated: "It is undeniable that an apology is due to the indigenous peoples of India based upon the same principles of justice and due to the inflicting of the same harm ... to an even greater degree, than in Canada."

Sharma noted that the Canadian apologies were "inadequate in many areas" and needed "extension and modification in order to accommodate the history of the Anglican Church and its adherents in British Occupied India," even though the "apology has started the process of dialogue and may one day result in a genuine healing."

Calling Dyer "a white supremacist and devout Anglican" and "a war criminal yet honoured upon his return to the United Kingdom" who "drove Indians to slaughter their own unarmed and vulnerable," Sharma said that he and other Hindu bodies, "are in agreement that there is a need for a Truth and Reconciliation Council to address the actions of Anglican's (sic) in India during the period of occupation."

Sharma's letter also underlined "the devastating assault on the indigenous Dharmic (Hindu) identity" and "the deeply destructive spiritual harm which was visited upon them for over two centuries." India was now gradually recovering under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, he added.

Sharma further asked for an audience with Welby where he and a delegation of Hindus could present the archbishop with the Mauritius Dharma Declaration.

In a video interview, Sharma warned Welby not to imitate the colonial Viceroys who were treated like gods when they visited India, "especially now, when most of the world is beginning to understand that what was done by the Anglicans when they last came to India in that manner was a horrific act of cultural and spiritual and physical genocide."

On the first day of his India tour, Welby struck a conciliatory note with British Hindus. He wrote in The Times: "If, as a Christian, I am serious about the common good, then I must speak for, and on behalf of, all religious minorities here in Britain, including Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. Meeting their communities and their leaders in India will give me the chance to forge those friendships."

However, prominent Indian Hindu nationalists mocked Welby's apology at Jallianwala Bagh, where 379 civilians were killed. Dr. Swapan Dasgupta, a distinguished member of India's parliament, called Welby's apology "a form of self-flagellation that may appeal to multiculturalism ... but doesn't alter the way India thinks of contemporary Britain."

According to historians, far from promoting Anglicanism or any other form of Christianity in India, the "ever cautious and pragmatic" British East India Company "studiously avoided tampering with religious institutions."

Its "policies of 'non-interference' and 'religious neutrality' aimed to demonstrate to all in India that their Raj was neither 'Christian' nor in favour of missionaries," writes Professor Robert Frykenberg in Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present.

Only after considerable pressure from William Wilberforce, Charles Grant, and the Clapham Sect did the British Parliament agree to send 'missionary chaplains' to India--and these had to limit themselves to serving British staff in India. Only in 1813 did parliament partially lift the ban on missionaries entering India.

"The Indian Empire was, fundamentally if not formally, a Hindu Raj," observes Norman Etherington in Missions and Empire.

Historians have also observed how Dyer, far from being a devout Anglican, proudly submitted to being made an "honorary Sikh" by other Sikhs after committing the massacre.

"General Dyer and Captain Briggs were invested with the five kakas, the sacred emblems of that war-like brotherhood, and so became Sikhs. Moreover, a shrine was built to General Dyer at their holy place, Guru Sat Sultani, and when a few days afterwards came the news that the Afghans were making war upon India, the Sikh leaders offered the General ten thousand men to fight for the British Raj if only he would consent to command them," noted Ian Colvin in The Life of General Dyer.

END