The Bible and Science (Part 3): Reading the Bible as a Christian

By Alice C. Linsley

Special to VIRTUEONLINE

www.virtueonline.org

December 17, 2017

In Part 1 of this series we considered this question: If Scripture is reliable and the empirical method is valuable, shouldn't the two work together for those who want to understand the Bible?

It is an error to think that biblical assertions cannot be tested by science. The Bible makes extraordinary assertions that can be found to align with the findings of different fields of science: anthropology, archaeology, astronomy, climate studies, DNA studies, linguistics, etc. In an age when it is generally assumed that the Bible is nonsense, identifying the alignments is an essential task of Christian apologetics.

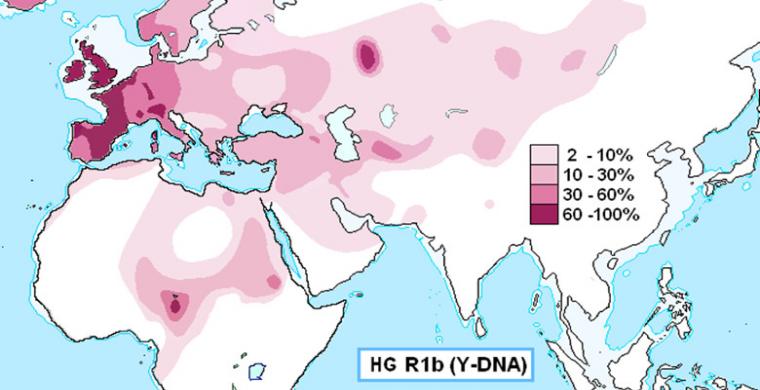

Approaching the Scriptures with an empirical eye involves noticing details that clarify the context and the meaning. We should note that Nimrod was a Kushite kingdom builder (Genesis 10:8) because this speaks of the Kushite migration out of the Upper Nile Valley, something that has been confirmed by DNA studies of Haplogroup R1b.

Linguists and Bible scholars have noted that many of the roots (radicals) found in the early chapters of Genesis are Nilo-Saharan roots and date to a time when the Sahara was wet. This suggests that Noah, Nimrod's great grandfather, probably lived in Africa during the time when it was prone to floods. That would make Noah a Proto-Saharan ruler. Interesting information has come forward about Proto-Saharan rulers. They kept royal menageries, and the animals were brought in pairs, a male and a female, in hopes that the species would reproduce.

The anthropological tools of kinship analysis have identified the rulers of Genesis 4, 5, 10, 11, 25 and 36 as historical persons with an authentic marriage and ascendancy pattern. Their kinship pattern is identical to that of Moses's family. This suggests that Cain, Seth, Lamech, Noah, Methuselah, Abraham, Sheba, Seir the Horite, and Moses share a common ancestral tradition.

Archaeological research reveals that this common ancestral tradition expressed itself in burial practices that suggest the hope of resurrection and immortality. Among those practices are the mummification of rulers, burial in red ochre (an archaic symbol of blood), and monumental tombs and temples with entrances aligned to the rising sun.

In Part 2, we focused on the relation of faith and science, and considered this question: Does faith play a role in scientific research and how Christians interpret data?

There is no doubt that faith informs our worldview and we filter data through a faith template. We may argue over questions of inerrancy, human agency, seeming contradictions, etc., but most Christians are confident that the Bible has been divinely superintended over the centuries. If we believe that the Bible is divinely superintended, we may trust that the biblical data can stand up to empirical investigation.

Attitude is important when reading the Bible. If we approach the text seeking ammunition to fight for a cause, we will fail to understand the divine message. If we approach in arrogance, we will find nothing of real value. The best stance when approaching the Bible is humble inquiry, as a beggar seeking entrance to the King's palace.

In this installment, we explore how a Christian should read the Bible in the face of secular challenges.

Focus question: In an age that challenges the assertions of the Christian faith, how should Christians read the Bible?

The short answer is that we should be like the noble Bereans who investigated the Scriptures to see if these claims be true (Acts 17:11). Investigation means digging deep into the text, not reading a commentary on the text. It means questioning the text, not taking it for granted. It means recognizing that the Bible does not answer all questions, only the essential ones. It means making a lifelong pursuit of the mysteries of God that are hidden in Jesus Messiah. True students of the Bible are like scientists for whom every answered question leads to new questions. Discovery leads to further discovery.

Anselm of Canterbury approached truth with the right attitude. He wrote, "For I do not seek to understand in order that I may believe, but I believe in order to understand. For this also I believe - that unless I believe I shall not understand."

The Hubris of Scientism

Arguments among Christians arise over a text or a doctrine when people insist that their interpretation alone is the correct one. Such dogmatism is not unique to Christians. We find it among scientists who believe that science alone confirms truth. This "Scientism" was exposed as fraudulent by the late Dr. Austin Hughes in "The Folly of Scientism" (The New Atlantis, Feb. 2012). He wrote:

When I decided on a scientific career, one of the things that appealed to me about science was the modesty of its practitioners. The typical scientist seemed to be a person who knew one small corner of the natural world and knew it very well, better than most other human beings living and better even than most who had ever lived. But outside of their circumscribed areas of expertise, scientists would hesitate to express an authoritative opinion. This attitude was attractive precisely because it stood in sharp contrast to the arrogance of the philosophers of the positivist tradition, who claimed for science and its practitioners a broad authority with which many practicing scientists themselves were uncomfortable.

The temptation to overreach, however, seems increasingly indulged today in discussions about science. Both in the work of professional philosophers and in popular writings by natural scientists, it is frequently claimed that natural science does or soon will constitute the entire domain of truth. And this attitude is becoming more widespread among scientists themselves. All too many of my contemporaries in science have accepted without question the hype that suggests that an advanced degree in some area of natural science confers the ability to pontificate wisely on any and all subjects.

Of course, from the very beginning of the modern scientific enterprise, there have been scientists and philosophers who have been so impressed with the ability of the natural sciences to advance knowledge that they have asserted that these sciences are the only valid way of seeking knowledge in any field. A forthright expression of this viewpoint has been made by the chemist Peter Atkins, who in his 1995 essay "Science as Truth" asserts the "universal competence" of science. This position has been called scientism -- a term that was originally intended to be pejorative but has been claimed as a badge of honor by some of its most vocal proponents. In their 2007 book Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized, for example, philosophers James Ladyman, Don Ross, and David Spurrett go so far as to entitle a chapter "In Defense of Scientism."

Today the challenges to our Christian faith are so great that we can’t be complacent about the claims of Scripture. We must counter ignorance of the text with clear and concise evidence. If a claim is true there will be evidence to that effect. Investigate the claim! We can no longer accept something by faith. We must also confirm it by every possible means, and God will help us in the pursuit of truth.

Christians are to demonstrate that the Bible is more than an account of irrelevant past events. We do this by reading the Bible daily and reflecting on its application. We do this by taking it as our primary authority for faith and practice. If we are to rise to the challenges of secularism and scientism we must also read empirically. That means identifying and verifying the accuracy of biblical data so that the world may know that the supernatural message of the Bible is written everywhere in the natural world (Romans 1:20). As St. Jerome reminds us, “Ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ!”

Alice C. Linsley teaches the history of technology and science at a Christian School in North Carolina. In this series she makes a case for an empirical approach to the study of Scripture. Her area of concentration is Biblical Anthropology. She comes from a long line of clergy, philosophers, and scientists. Two famous chemists named in this first installment - Robert R. Williams and Roger J. Williams - are her great uncles.