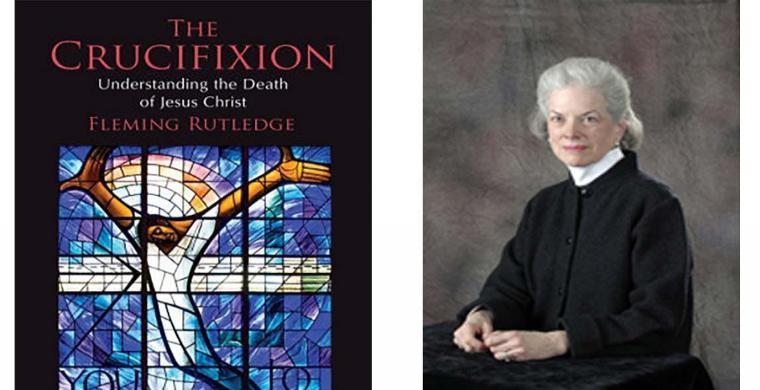

THE BLOOD-SHEDDING: PART FOUR

Concluding thoughts on the theology of Fleming Rutledge

By Roger Salter

Special to Virtueonline

www.virtueonline.org

August 21, 2018

It appears more and more in the consideration of The Crucifixion by Fleming Rutledge that her theological effort is tantamount to the smuggling of dangerous wares into the territory of Christian thought. Not that she alone is the manufacturer or purveyor of these wares but that they are made more enticing in that they are bundled into a container (her book) with other stock of an innocent or even beneficial nature that is likely reduce the necessary wariness of an unsuspecting recipient. It is as if the artful packaging and wrappings of her fundamental ideas suggest wholesome content. Her presentation comes to us under the guise of orthodoxy.

Her essential campaign, whether conscious or not, seems to be to de-personalize the guilt of individual human sin and assign responsibility for evil principally to the cosmic powers opposed to God, and oppressive toward man, which tendency happens to produce a lopsided emphasis on Christus Victor(an undoubted vital factor in an overall view of the atonement) and a strong tendency seriously to downplay the absolute necessity of penal substitution specifically. A second baleful tendency is the advocacy of the theology of Karl Barth as the necessary overhaul and improvement of more traditional Reformed theology. In the final analysis the doctrinal formulations of Barth are non-substantive, illusory, incomprehensible, and the inventions of a mental magician as he strives to restyle articles of faith such as the Word of God, and the significance and work of Christ, demote personal faith, ultimately to lodge creedal correctness, in some vague way, in the Christian community.

Every step with Barth is to encounter mirage after mirage that vanishes whenever you endeavor to take it into grasp. Every major thought of Barth gives scope for conceptual gymnastics (which academics revel in) in that, "This is that, but 'that' is not quite 'that', and really, 'that' is ultimately elusive, but "that" must be authorized by "this" which in reality is merely provisional, but Barth can certify it as truth. But on the other hand, the issue must be left open so as not to trespass upon the divine sovereignty, which winds up as saying, "We don't really know, but treat what you think you know as the truth". The outcome is 'voluble verbiage' that conceals bewilderment. True and plain gospel preaching perishes.

With The Crucifixion - which does challenge Christian attention to the atonement to greater breadth and comprehensiveness in consideration of the biblical data - penal substitution is in peril. With The Crucifixion Christus Victor assumes foremost place and with its guiding notions found in its leading proponent Gustaf Aulen we encounter imbalance and omissions as noted by Leon Morris in his indispensable volume The Cross in the New Testament.

'Such a great scholar as G. Aulen can say, "Justification and atonement are really one and the same thing. Justification is simply the Atonement brought into the present so that here and now the Blessing of God prevails over the curse." This is simply not true. Justification has a meaning of its own and that meaning must be sought carefully. That Christ's work for men can be described in terms of atonement, or blessing, or curse, does not give a license to equate justification with any of these terms' (page 241). It is interesting to observe, also, that Rutledge sees the crucifixion as removal of the curse of the powers but not as the removal of punishment for sin which demands a penal substitute absolutely. Christus Victor should be an ally of penal substitution and not a substitute conceptually.

Morris states that Christ's "manhood was an essential qualification for the offering of the propitiatory offering", whereas, "Aulen overlooks the significance of Christ's manhood in the work of atonement. He admits that there are two aspects, but all his emphasis is on the one . . . he stresses the act of Christ as God . . . One looks in vain for any real treatment of the significance of Christ's manhood." As a result of this omission the fact of penal substitution is the casualty. Morris comments that it is right for Aulen to warn against a one-sided stress on the manhood - "Jesus the man offers the propitiation, while the Father does little more than accept it. This opens the way for a cleavage in the Godhead" (Morris) - but Morris continues, "there is also harm done when it is insisted, as it is by Aulen himself, that the atonement is all of God. Though he sometimes speaks of the human element in Christ's offering this theologian puts all his emphasis on the divine. Over and over he insists that the atonement is from first to last God's work. He concentrates on the theme that God in Christ has won the victory over all the forces of evil. The manhood of our Lord has no real part to play in the work of atonement. The incarnation seems to be meaningless, at least as far as the atonement is concerned" (pp.373-4).

The pure and virtuous humanity of the God-man displayed in his total obedience to the will of the Father - even in submission to an innocent death - as making amends, as man, for the disobedience of men is overlooked. Christ not only died to conquer the fiends and powers of hell but to provide a righteousness for sinners: He was delivered over to death for our sins and was raised to life for our justification (Romans 4:25).

Leon Morris is scrupulously fair in his assessment of proponents of various leading "theories" of the atonement. It is vital that our comprehension of the crucifixion should be as comprehensive as Scripture informs. The "Johnny One-note" approach is not sound. "[Similarly} upholders of the penal theory have sometimes so stressed the thought that Christ bore our penalty that they have found room for nothing else. Rarely have they in theory denied the value of other theories, but sometimes they have in practice ignored them. In recent years Aulen has done much the same in his insistence on 'his' classic view. The paying of penalty, the offering of sacrifice, and the rest are discarded. Victory is all that matters" (p.401). The advocates of Christus Victor seem to imply that Christ's deliverance of humanity from "the curse" is not the curse of our sin and its penalty, but the curse of the wicked and hostile powers and the harm that they wreak.

The virtual universalism traced throughout The Crucifixion tends to derive in the main from Paul's words in Romans 5 concerning the first and second Adam: "Consequently, just as the result of one trespass was condemnation for all men, so also the result of one act of righteousness was justification that brings life for all men" (v18). The interpretation of this passage is an instant where context and salvific logic come into necessary play. Given Paul's constant distinction between those in union with Christ through faith and those remaining in the grip of unbelief and therefore liable to judgment, it is unthinkable that he actually teaches the justification of all without exception, either in this life or at the point of the judgment. Differentiation between two groups of persons is maintained consistently in the thought of the apostle. Douglas Moo discusses the linguistics and theology of this matter very thoroughly in his commentary on Romans over several pages that fully deserve perusal. The whole sense of Scripture here and elsewhere makes his ultimate conclusion inevitable.

'That "all" does not always mean "every single human being" is clear from many passages, it often being clearly limited in context (cf., e.g., Rom. 8:32; 12:17,18; 14:2; 16:19), so this suggestion has no linguistic barrier. In the present verse, the scope of "all people" in the two parts of the verse is distinguished in the context, Paul making it clear, both by his silence and by the logic of vv12-14, that there is no limitation whatsoever on the number of those who are involved in Adam's sin, while the deliberately worded v. 17 along with the persistent stress on faith as means of achieving righteousness in 1:16 - 4:25, makes it equally clear that only certain people derive the benefit from Christ's act of righteousness' (pp. 343-344).

The very exact theologian and linguist William G.T. Shedd endorses the view of Douglas Moo. "The meaning of 'all', equally with that of "many", must be determined by the context. Compare xi. 32; 1 Cor xv. 22. The efficacy of Christ's atonement is no more extensive than faith; and faith is not universal (2 Thess. iii.2).

Shedd adumbrates the differences between humanity in union with Adam and the union between the new humanity and Christ Jesus. This latter union through divine grace, "differs in several important particulars from that between Adam and his posterity. It is not natural and substantial, but moral, spiritual, and mystical; not generic and universal, but individual and by election; not caused by the creative act of God, but by his regenerating act. All men without exception are one with Adam, only believing men are one with Christ. The imputation of Christ's obedience, like that of Adam's sin, is not an arbitrary act, in the sense that if God so pleased he could reckon either to the account of any beings whatever in the universe, by a volition. The sin of Adam could not be imputed to the fallen angels, for example, and be punished in them; because they never were one with Adam by unity of substance and nature . . . Nothing but a real union of nature and being can justify the imputation of Adam's sin. And similarly, the obedience of Christ could no more be imputed to an unbelieving man, than to a lost angel, because neither of these is morally, spiritually, and mystically one with Christ. Not all mankind, but only those persons who are described in verse 17, as 'they which receive abundance of grace, and of the gift of righteousness.'"

Among many other points of dissimilarity between mankind's union with Adam and new mankind's union with Christ Shedd offers this conclusion. "The imputation of Adam's disobedience is necessary. All men have participated in it, and hence all men must be charged with it. The imputation of Christ's obedience is optional. No man has participated in it, and whether it shall be imputed to any man, depends upon the sovereign pleasure of God" (Romans pp. 136 - 142).

There is a qualitative difference between the "all" of Adam and the "all" of Jesus Christ.

The Barthian notion of recapitulation championed in The Crucifixion, plus the dominant influence of the classic theory of the atonement, evacuate the gospel of so many essential elements that hinder its impact upon, and reduce the benefits of the word of God toward the Christian believer. Consequently, several key concepts of Scripture are in jeopardy, namely, the reality of the birth from above as the indispensable commencement to life in Christ, the necessity of living faith in the true child of God, and the real nature of Justification. The reality of justification as acquittal (not rectification) necessitates forensic terminology which so offends Rutledge that she opines, "That the model of penal substitution as it has been widely taught in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries should be re-thought and revised. . . . Indeed there is good reason to question the biblical character of the model. For instance, Hodge [Charles] used expressions like 'forensic penal satisfaction' which does not sound remotely like anything in Scripture". It's not a long stretch, in the reading of Scripture, to arrive at an agreement with the Hodges and Dabneys and later scholastics of Protestantism. The biblical descriptions of the evil condition of our race, the biblical depictions of he wrath of God, and the biblical delineation of the divinely devised way of salvation point to Hodge's language as fully appropriate.

Dispersed throughout her much lauded volume there are expressions that illuminate Rutledge's departure from biblical imperatives: the urgency of the gospel for people in peril, the consolations of the gospel for people of faith, the utter reliability of the word of God - not in sweeping generalizations and spurious speculation - but in the specific details of Scripture read text by text in the quest for their full value under the tutelage of the Holy Spirit. To be simplistic, we do not say with Karl Barth, "you are all likely to be saved - you just do not know it yet". Even 95% universalism is extremely hazardous. It risks souls that should be awakened, and assures folk that salvation is present where faith is absent. It is careless theology that encourages careless living and a careless approach to death.

Whatever the perceived merits of The Crucifixion, even from high class academics, in the eternal scheme of things it is misleading and an unfortunate omen for the future preaching of the gospel should the author secure a wide following.

Great St. Anselm accords us maximum consolation from the Gospel:

Dost thou believe that thou canst not be saved but by the death of Christ? Go to, then, and whilst thy soul abideth in thee put all thy confidence in his death alone - place thy trust in no other thing- commit thyself wholly to his death - cover thyself wholly with this alone - cast thyself wholly on his death - wrap thyself wholly in this death. And if God would judge you say, "Lord! I place the death of our Lord Jesus Christ between me and thy judgment: otherwise I will not contend, or enter into judgment, with Thee. And if he shall say unto thee that thou art a sinner say unto Him, "I place the death of our Lord Jesus Christ between me and my sins." If he shall say unto thee, that thou hast deserved damnation, say, Lord! I put the death of our Lord Jesus Christ between Thee and all my sins, - I offer his merits for my own, which I should have and have not. "If He say, that he is angry with thee, say, "Lord! I place the death of our Lord Jesus Christ between me and thy anger.

This is the place of refuge and joy for the sinner, and without reference to the foregoing, but in happy continuance grammatically, the great lover of Isaiah, and indeed, the entirety of Scripture, Alec Motyer writes in his book Isaiah By the Day:

In this place, too, we discover how marvelously secure we are in Christ. Through him as Mediator we come to the Father, and, knowing partially but terrifyingly, all that unfits us for his presence and fits us for his wrath, we find ourselves in the presence of love beyond anything known on earth, and the voice which says, 'I was delighted when my Son died for you - and I am still delighted.'

The Rev. Roger Salter is an ordained Church of England minister where he had parishes in the dioceses of Bristol and Portsmouth before coming to Birmingham, Alabama to serve as Rector of St. Matthew's Anglican Church.