English Reformers were Unashamed Moderate Calvinist

By Chuck Collins

www.virtueonline.org

August 31, 2023

Anglicans have a peculiar theology based on the "formularies." The formularies teach that humankind is sinful by nature and unable to turn to God apart from God acting towards them, that the saved are elected and predestined for such a relationship, and that salvation is a free gift of God's grace obtainable by faith alone.

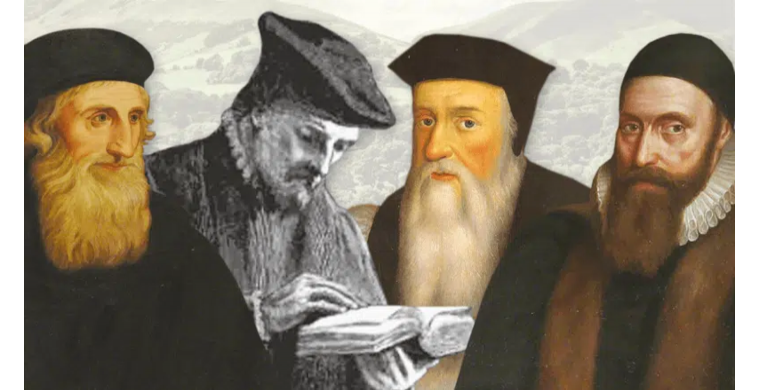

In short, the English reformers and the Church of England established (the Edwardian and Elizabethan Settlement) were unashamed Calvinist in their core theological beliefs. It wasn't so much that Thomas Cranmer, the principal author of the formularies, followed Calvin as much as Calvin and Cranmer both followed the Scriptures to the same irrefutable claims about man's need and God's provision.

But after substantial consistency around the Settlement and the established formularies for the first generation of Anglicans, the anti-Calvinists, Arminians, established a foothold in the church and they have continued to dig in ever since. With their message of free will and their disdain for predestination, the I-have-decided-to-follow-Jesus Christianity of the Arminians fueled the Laudian high Church movement and the accompanying rise of moralism, and arguably every other theological aberration to hit the Church of England, all of them conflicting in some way with the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, and the two books of Homilies.

So, how is it that the Church of England started with a firm commitment to moderate Calvinism (Calvin before Calvinism - the message of the Anglican formularies), but after the reigns of Edward VI, Elizabeth I, and James I the colors of the church changed to Arminianism (often called Pelagian: see Article 9)? By the 1630s-40s the church became significantly anti-Calvinist and has remained largely that ever since, and I wonder why and how it happened.

Does this explain the hair-shirt relationship Anglicans sometimes have with its Calvinistic formularies? And what explains the shift from the high christology of salvation by grace through faith alone, to the high anthropology (moralism) of Laud, Hammond, and Taylor 100 years after the English Reformation - that manifested itself in high church movement - that then led to the holiness movement of John Wesley - and on to modern expressions of Arminianism that are found in forms of pietism, mysticism, and the spiritual disciplines movement?

The bedrock theological question that underlies all is this: Is Jesus the Savior of all who choose to choose him, or is our eternal destiny predestined, individual, and absolute from "before the foundations of the world were laid" (Article 17)?

The psychology of Arminianism (decisionism, revivalism, moralism, progressivism, and a generally sunnier outlook on human capacity) appeals to the most base elements of human nature - on some level we all love the idea that performance and self-righteous advancements contribute to our salvation. This default human position has its earlier expression in fifth-century Pelagian heresy and the bald semi-pelagianism of the Medieval Catholic Church. But as a brand, Arminianism was born in Holland at the turn of the 17th century in reaction against Calvinism. It was repudiated by the reformed world, including the Church of England at the Council of Dort (1618), but it obviously lives on.

Arminians and Calvinists both believe in predestination; they have to, the Bible teaches it! Arminians teach that predestination is corporate and not individual (Israel and the new Israel, the church). Calvinists (Reformation Anglicans), on the other hand, believe that "predestination to Life is the everlasting purpose of God, whereby (before the foundations of the world were laid) he hath constantly decreed by his counsel secret to us, to deliver from curse and damnation those whom he hath chosen in Christ out of mankind, to bring them by Christ to everlasting salvation, as vessels made to honor" (Article XVII).

J. I. Packer wrote, "Arminians praise God for providing a Savior to whom all may come for life; Calvinists do that too, and then go on to praise God for actually bringing them to the Savior's feet." Reformation Anglicans don't believe that God's love stops at the point of politely inviting, but that God takes the additional gracious action to ensure that the elect respond. Jesus said, "No one comes to me unless the Father who sent me draws him" (Jn 6:44). Arminians say that personal faith is the ground of justification; Reformation Anglicans say that justification is the ground of our faith.

Both Armenians and Calvinists believe in God's righteousness for salvation - they have to, it's in the Bible! Arminians believe that Christ's death and atonement made salvation possible "for all who will receive him," and that God's righteousness (his grace) is distributed incrementally over time so that we will become acceptable to the groom as his bride. High Church Arminians came to believe, as Roman Catholics do, that this infused righteousness is automatically delivered in the sacraments.

Reformation Anglicans also share the belief that it is God's righteousness that saves, but they see it as God's very own righteousness that is imputed to undeserving sinners - the robe of God's righteousness, his garment of salvation so completely covers our unrighteousness that God sees us forever as the righteousness of God (Isa 61:10; 2 Cor 5: 21). "We do not presume to come to this thy table, O merciful Lord, trusting in our own righteousness, but in thy manifold and great mercies" (Cranmer's Prayer of Humble Access).

Since Arminians focus on someone's personal decision for Christ (that awful song, "I Have Decided to Follow Jesus"), they have a very different view of assurance and heavenly security than do Reformation Anglicans. They see God's grace as resistible and that election to salvation is conditional on faith in Christ.

They are in and out of grace depending on their faithfulness to trust in God for salvation (that horrible song, "Trust and Obey"). This "led inevitably to a new legalism of which the key thought was that the exerting of steady moral effort now is the way to salvation hereafter" (Packer). On the other hand, Reformation Anglicans believe that eternal security is about God's faithfulness, not theirs, and since God and his promises are absolutely trustworthy, we can have absolute assurance. "For I am convinced . . ." "And I am sure of this . . ." (Rom 8:38-39; Phil 1:6).

William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury under King Charles I, helped open the door to Arminianism and all its iterations and complications, including the high church movement. He gave the preferred episcopal positions to Arminian cronies. Under him, worship in the Church of England was embellished with ceremonial and ritual that, for theological reasons, was not permitted after the Reformation.

Laudians brought back altars to supplant pulpits in liturgical importance, and Holy Communion became a priority over the preached word. Laud infamously said, "in all ages of the Church the touchstone of religion was not to hear the word preached but to communicate" [receive Holy Communion].

The battle for Anglican identity obviously continues today. It's evident in the "Yeah, but . . ." way many Anglicans respond to the formularies. And it is evident in the manipulated commentaries on the Articles of Religion, many of them written to justify preexisting theological preferences rather than "taken in their literal and grammatical sense" (ACNA's Constitution and Canons) - for example Edward Harold Browne's treatment of Article 17 as "ecclesiastical election," not individual. What is at stake is our core Anglican identity, but more importantly, the glory and sovereignty of God.

Either we are capable of reaching up to God in our own choosing and we just need a coach, or we are dead in our trespasses and sins and we need a Savior who has already defeated death.

Either the responsibility falls on us to raise our hand with all heads bowed and eyes closed, or God chose us from before the foundations of the world to be his children, and he who began that work in us will bring it to completion.

Reformation Anglicans see that salvation is wholly of God from beginning to the end - a free gift of sovereign mercy for people who don't deserve it, who haven't done enough to earned it, and who would never have eternal life had God not supplied what is needed in the life, death, and resurrection of his Son Jesus Christ our Lord. As the old hymn says:

I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew

He moved my soul to seek him, seeking me;

It was not I that found, O Savior true,

No, I was found of thee.

Thou didst reach forth thy hand and mine enfold;

I walked and sank not on the storm-vexed sea,--

'Twas not so much that I on thee took hold,

As thou, dear Lord, on me.

I find, I walk, I love, but, O the whole

Of love is but my answer, Lord, to thee;

For thou wert long beforehand with my soul,

Always thou lovedst me.