Episcopal Church schism enters new chapter of uncertainty after court ruling

By Adam Parker and Jennifer Berry Hawes

Post & Courier

http://www.postandcourier.com

August 5, 2017

In the aftermath of the S.C. Supreme Court's ruling Wednesday on the dispute between The Episcopal Church and a breakaway diocese, many parishioners, clergy and others with a vested interest in Anglican life are wondering when -- or whether -- another exodus will occur.

The court decided in a set of five distinct opinions that most of the church buildings in the Diocese of South Carolina, as well as Camp St. Christopher on Seabrook Island, belong to The Episcopal Church. These properties include historic parishes such as St. Michael's and St. Philip's downtown, Old St. Andrew's in West Ashley and Christ Church in Mount Pleasant, as well as buildings in Beaufort, Edisto, Summerville, Georgetown, Myrtle Beach, Florence and elsewhere in the coastal half of the state.

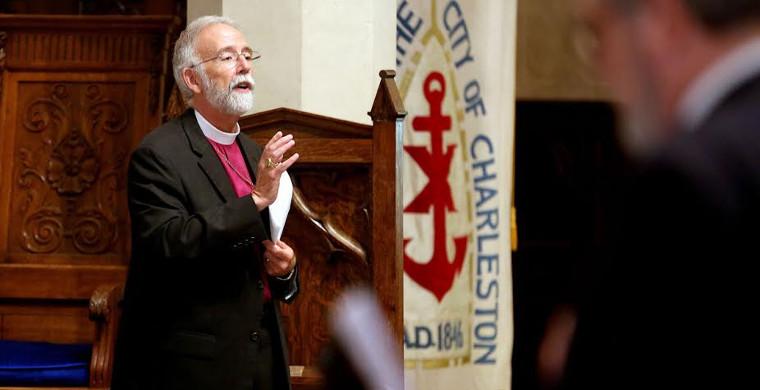

The Diocese of South Carolina under the leadership of Bishop Mark Lawrence was granted an extension on Friday for filing a request for a rehearing, giving lawyers 30 days to submit their petition with the S.C. Supreme Court.

If granted the petition, attorneys will argue the case again, this time before a court whose members have partially changed. If the petition is not granted, the Diocese of South Carolina still can submit a writ of certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court, asking for its intervention. The high court generally has not chosen to hear cases of this type in the past.

At Grace Church Cathedral in downtown Charleston, leaders of The Episcopal Church in South Carolina gathered Friday to discuss the S.C. Supreme Court opinions and then attended a prayer service.

The Very Rev. Michael Wright, rector and dean of Grace Church, said the cathedral has served as "a refuge from the storm" for many, gaining a large number of worshipers from parishes that left The Episcopal Church. They must now contemplate "the next phase" in the life of the diocese, he said.

That phase holds much uncertainty, said Bishop Skip Adams.

"We have made no decisions," Adams said. "We came together to express faithfulness, to worship together and to have a chance to hear from folks."

Most people came to the meeting with the question, "Where do we go next?" But there are no answers yet, and rumors and speculation are not helpful, he said. Instead, he called on his colleagues to acknowledge the pain on both sides and to keep paths as wide open as possible.

"In the middle of it all, we still have our mission: to share the Good News, to worship together" and, as the catechism in the Book of Common Prayer states, to restore all people to unity with God and each other in Christ. "Our goal still is reconciliation."

In the meantime, they wait.

"That's the hard part," Adams said.

What has happened

The Diocese of South Carolina under the leadership of Bishop Mark Lawrence left The Episcopal Church in 2012 after years of wrangling over theological and administrative issues. Lawrence and most of the diocesan leadership disliked what they considered The Episcopal Church's emphasis on political correctness and inclusiveness over sound Christian doctrine.

The dissatisfaction was exacerbated by the 2003 consecration of Gene Robinson in New Hampshire, the church's first openly gay bishop. The gap of disagreement became a chasm as Lawrence and other like-minded Anglicans within the church tussled with then-Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori, whose church continued to address issues of equality and diversity.

In the years that followed, congregations in four other Episcopal dioceses -- San Joaquin, California; Quincy, Illinois; Fort Worth, Texas; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania -- split from The Episcopal Church, as well as several individual parishes, all claiming ownership of their properties.

When the Diocese of South Carolina followed suit, it too kept control of the church buildings, as well as Camp St. Christopher. It also retained intellectual property such as the name of the organization and its seal, forcing those still associated with The Episcopal Church's local diocese to come up with a new name: The Episcopal Church in South Carolina.

Lawrence's group, which far outnumbered the Episcopalians left in the continuing diocese, eventually joined the Anglican Church in North America but maintained its identity as a distinct organization.

Those who chose to remain with The Episcopal Church often found themselves with no sanctuary in which to worship. Their congregations, now a fraction of their former sizes, convened in borrowed spaces, and many soon formed mission churches in need of permanent buildings.

In 2015, the officials of the continuing diocese of The Episcopal Church proposed a settlement to the disaffiliated diocese that would have enabled Lawrence's group to retain 35 church properties, worth hundreds of millions of dollars, in exchange for Camp St. Christopher, the identifying marks and other assets. But the breakaway group argued the offer was an illegitimate "public relations illusion," not a proper offer made in good faith. The legal battle raged on.

Wait-and-see approach

The court's ruling will have profound implications on thousands of clergy and congregants, many of whom could face difficult decisions over whether to stay or leave their physical church homes.

Archbishop Foley Beach of the Anglican Church in North America called for a day of prayer and fasting.

"Many of you have heard of the mixed decision by the South Carolina Supreme Court, ruling that most of the parishes in the Diocese of South Carolina may have to turn over their properties to the Episcopal Church," he wrote in a pastoral letter on Thursday. "The legal process is still unfolding and I am asking you to join me in a day of prayer and fasting for the Diocese on this Friday, August 4."

Charles W. Waring III has worshiped at St. Michael's Church, the oldest church structure in Charleston, for almost his entire life. His family's legacy at St. Michael's reaches back about four generations, so the parish isn't just a building to him, he said. Its walls hold a lifetime of memories and the whispers of his ancestors.

The Supreme Court ruling, however, doesn't worry him yet.

"It took years to get to this point. I'm not expecting we'll be going to church on Sunday and have police tape around the building," said Waring, publisher of the Charleston Mercury, which once was affiliated with The Post and Courier.

The legal battle isn't over and, in any case, reasonable people on both sides will come to a resolution that respects everyone, he said. For now, he will focus on worshiping where his family has prayed since the end of the Civil War.

"It's full of meaning and memories, but the congregants are my primary focus, along with the faith message," Waring said.

Maybank Hagood grew up attending historic St. Philip's Church downtown and raised three children there with his wife, Elizabeth. He has relatives buried in the picturesque graveyard.

"It's a beautiful, historic place," Hagood said. "But it's a lot bigger for us. It's a church community, a body of Christ we've lived with and worshiped with our whole lives."

Instead of worrying about the impact of the court ruling, he has tried to take a wait-and-see approach to the property's future.

"This has been going on for a long time," Hagood said. "The court process is going to have to play itself out." Like Waring, he believes that the faithful on both sides will reach an agreement.

Tough decisions ahead

Jean Bender, canon for pastoral care at Grace Church Cathedral, said the schism has been traumatic for many on both sides.

"It didn't only split the diocese, it split families," she said.

News of the court's decision was soothing to some but it also served as a sudden reminder of the distress endured by many.

"There was a PTSD-type response for some because of the pain they've been through," she said.

Bender identified three main groups of people in most parishes affected by the schism: a group strongly opposed to The Episcopal Church and its liberal theology, a group strongly loyal to The Episcopal Church and a group somewhere in the middle whose members do not necessarily embrace in full the theology and practices of either faction but prefer to remain in the building where they have long worshiped.

As this long legal battle eventually concludes, all of these people will need to decide what to do, she said.

*****

Church members continue on following court ruling on separation from Episcopal diocese

By Brad Streicher

WCSC LIVE 5 NEWS

http://www.live5news.com/

Aug. 6, 2017

CHARLESTON, SC -- Episcopal churches in Charleston that separated from the national Episcopal Church had normal services on Sunday.

That's despite the fact that the state Supreme Court ruled that the church structures don't belong to the churches themselves.

For St. Michael's church, Sunday was business as usual.

"We are so happy to gather here together and to worship as we do every Sunday," said Elizabeth Scarbourough, a member of St. Michael's.

"I come every day. I come every Sunday," said Jeffrey Moll, another member of the church.

But this Sunday was a little different than most.

"This is the start of the next chapter of the book and that we go into finding out where go from here," said Frank Farmer, a church member of St. Michael's.

St. Michael's is one of 36 churches in eastern South Carolina that broke away from the Episcopal Church.

Last week, the state Supreme Court ruled that many of the churches themselves do not own the buildings where they hold service.

That means the people at St. Michael's could have to find a new place to worship.

"We're all gathering as a core congregation of St. Michael's Anglican Church, discussing what that means for us, and where we move from here," Scarbourough said.

The people at St. Michael's say that losing the property wouldn't necessarily be the end of the world.

For them, church isn't about the building. It's about the people and practices inside.

"The church is the people," Farmer said."I mean that's what we've been taught, that's what we believe is that the people are the church, and not the building."

Farmer moved to Charleston in 1993 and at that time he didn't know anyone.

That changed because of St. Michael's.

"I found a family there," Farmer said."I started going in 2000. And that's what I would say is my family."

A family he's confident isn't going anywhere.

"If that is the outcome, then we'll go somewhere else," Farmer said."It's not the end of the family, it's not the end of the service. We'll continue somewhere, we'll find somewhere else to go. It just won't be here."

The Episcopal Church and the Diocese of South Carolina are giving each other 30 days to decide where the lawsuit between the churches will go from here.