Facing a schism: A bishop, gay marriage and the Episcopal diocese of Albany

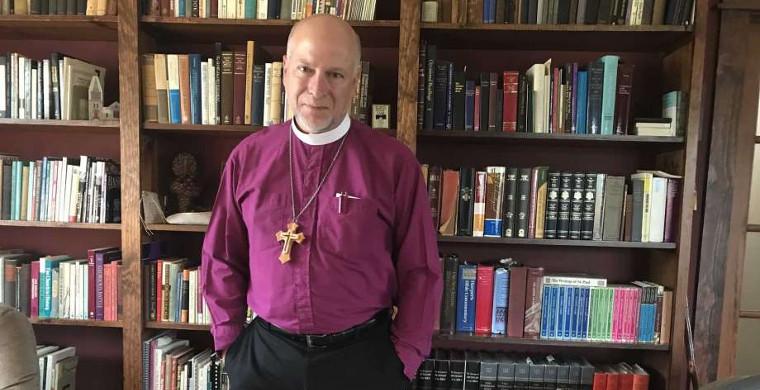

Photo: Bishop William Love (photo By Amy Biancolli)

By Amy Biancolli

https://www.timesunion.com/

September 1, 2018

For the last three years, gay Episcopalians in the diocese of Albany have been trapped in a canonical limbo. The national church sanctions same-sex marriage. The local church does not. The majority of American bishops support it. The local bishop does not.

And so, for the last three years, gay Episcopalians in search of a church wedding have traveled outside the diocesan lines to have one. Even those who assist with local nuptials can't marry here.

"You know, I'm the cathedral's florist," said Louis Bannister, a gay member of the Cathedral of All Saints on Elk Street. "I can arrange the flowers for anyone's wedding but my own."

Then, this past July, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church issued Resolution B012, a compromise aimed at allowing gay couples to marry at their home churches in the eight dissenting dioceses across the country -- Albany among them -- where gay marriage remained forbidden. In response, Albany Bishop William Love issued a soberly worded letter calling the resolution "problematic and potentially damaging," adding, "The vast majority of the clergy and people of the Diocese, to include myself, are greatly troubled by it."

He called for a special meeting of clergy -- scheduled for Thursday at the Christ the King Spiritual Life Center in Greenwich. What may come of it, no one knows -- not clergy, not laypeople, not Love himself, who sat for a two-hour-and-15-minute interview one Friday morning in August. From his standpoint he's the one now trapped in canonical limbo, "where our diocesan canons state one thing, and the General Convention says something else. And we have to figure out how to deal with that tension."

But no matter what their role in the church or where they stand on the issue of gay marriage, nearly all of the 19 people who commented for this story by phone or email described a diocese in the thick of complex, ongoing and difficult change. Love was blunt in his own assessment: "We're in the midst of a major schism."

From Love's vantage, and the vantage of those who support him, the Episcopal Church is to blame. The bishop sees B012 and the sanctioning of same-sex weddings in 2015 as a movement away from the broader Anglican Communion, which includes more orthodox churches -- in African countries, for instance -- that oppose the American episcopate's embrace of gay marriage.

From the vantage of those in the diocese who support same-sex weddings, Love's literal reading of that very scripture -- in the narrow light of an ancient definition -- is to blame. They see the bishop's position as a doctrinal refusal to budge that denies gays their full engagement with church life, failing to grasp parallels with earlier Episcopal prohibitions such as those against interracial marriage and the ordination of women.

From the vantage of both, the gulf is head-spinning and the questions are huge. Does the Bible contain God's literal word? What is marriage, anyway? "I think marriage is between two adult people that want to be married," said Joan Csaposs, a former congregant at the Cathedral of All Saints and the mother of a gay man. But what seems obvious to her isn't for everyone, "Because some people in the area are strictly stuck in what they believe."

Love knows he's been branded as one of the stuck. "What is frustrating to me is to be accused of failing to understand marriage, or whatever -- when, in fact, what I'm teaching is what the church has always taught, and what God has revealed through holy Scripture," he said. "The new understanding of marriage is a new thing, just within a matter of a decade or so."

Wearing the purple shirt and clerical collar of his position, the bishop spoke in hushed, unhurried but impassioned tones from his office in Greenwich. He spends part of his workweek there, part at All Saints, the rest traversing a diocese that stretches from Clinton and St. Lawrence counties to the north to Delaware and Columbia counties to the south.

He often meets with gay congregants and volunteers, setting aside any differences in belief. He said the injunction against gay marriage, or even gay sex, has no bearing on his regard for gays as human beings: Everyone is a sinner, himself included. If anything, he said, the Episcopal Church "is doing a great injustice" to gays, affirming their behavior and depriving them of a chance to repent.

"I would be the first to acknowledge that all people -- regardless of our gender, regardless of our understanding of our sexuality -- we are all created in the image and likeness of God," Love said. "And God loves every person that he has ever created, to include those who find themselves to be homosexual in orientation, or transgender, or bisexual, or whatever the orientation might be. He loves every one of us. That said, that doesn't mean that he approves of everything that we do."

"You know, it's 'love the sinner, hate the sin,'" agreed Ginny Ogden, pastor of the Church of the Good Shepherd in Canajoharie and one of several interviewed who made that distinction. While some of the Bible's more extreme mandates shouldn't be taken word for word, she said, "Just because the punishments have changed doesn't mean that God's moral laws have changed. You know, we don't stone people to death for adultery any more. But that doesn't mean God approves of adultery."

The old sinner/sin maxim baffles those who back gay marriage. "That never made sense to me. When I hear that, I'm thinking, like, 'What are you trying to get around?' I just don't understand," said Justin Lanier, rector at St. Peter's in Bennington, part of the more-progressive Vermont diocese.

One of the most-religious weddings he ever officiated, he said, was that of a gay couple who married at St. Peter's. They didn't come for the beautiful church interior. "They came for the sacrament, they came for the practice," he said. "They were engaged in the spiritual life of Christianity."

Love -- and, yes, people on both sides remark on his name -- said he takes no issue with gay orientation. He approves the idea of a civil union and affirms the legal protections afforded same-sex partners. And despite the stricture against same-sex marriage, Love says he has never denied gay Episcopalians the sacraments of communion, confirmation or baptism.

In addition, the bishop has been "very compassionate in his instructions to us in dealing with anyone who is gay or transgendered or anything like that," said Michael A. O'Donnell, rector at St. John's in Ogdensburg.

That said, Love believes gay people are called to celibacy -- just as heterosexuals who find themselves single are called to celibacy. Sex belongs in marriage, he said, and the Bible ordains that marriage can only occur between opposite-sex couples. A gay couple who love and support one another through several decades "can be in a faithful, monogamous relationship with one another, a loving relationship with one another," he said. "But it's not a marriage."

By Love's estimate, roughly 80 percent of his "theologically conservative" diocese would agree with him. For this story, press queries were sent to around 60 churches, roughly half the diocese; most did not respond. Of the eight diocesan clergy who agreed to speak or emailed their comments, the majority voiced support for Love and expressed admiration for his unwavering faith. Even those less firmly aligned with his views described his leadership as serious, prayerful and attentive to clergy's needs.

The large diocese includes churches from the Canadian border to the Pennsylvania border, forcing gay Episcopalians in the Albany area travel far to find an Episcopal Church where they can wed.

And most everyone interviewed, Love included, said they value unity. But most everyone professes their faith and opinions from a stance of unshakable conviction, much of it based on their interpretation of Scripture. Love and like-minded believers take relevant passages in the Old and New Testaments -- Leviticus, the letters of Paul, other sources -- as the unalterable word of God. Others take them as prohibitions shaped by human messengers and the patriarchal, procreation-centered attitudes of the era that bore them.

"There's 6 billion people on the Earth, and if God is divine, and we're all mortal, that means there's 6 billion interpretations of what God was saying when Scripture was created," said Don Csaposs, Joan's husband.

"I think there's a huge cognitive disconnect between the elements that are held up in defense of Bishop Love's position" and other elements that negate it, said Brandon Dumas, director of music ministry at St. George's in Schenectady and a gay man who grew up singing in the choir at All Saints. While the Old Testament has its laws of purity, he said, the New Testament conveys a message of love. "Taken today, the message of Jesus in his ministry would very soundly drown out everything else that's there on the printed page."

Love said he listens to such arguments, including those that claim a prophetic view for the Episcopal Church. He just isn't dissuaded. "I believe that the Bible is, in fact, the word of God. It's not just some historic document that was written some 2,000-plus years ago, but it is God's revealed word." He declared as much when first ordained a deacon, then a priest, then a bishop. "And so one of the struggles that we're having in this conversation about human sexuality is that so many of the folks who are promoting this don't have the same understanding of the Bible."

Speaking in Greenwich that Friday, Love quoted scripture. He quoted prayers and liturgies, flipping through the Book of Common Prayer -- the core collection of teachings and devotional texts used throughout the Anglican Communion and its 45 churches. The Episcopal province covers the United States, Taiwan, bits of Latin America and elsewhere: the word itself, from the Latin episcopus, or bishop, underscores the traditional importance of diocesan leadership.

Unlike other Protestant sects, which emphasize decision-making in individual congregations, the Anglican Communion gives authority to bishops. This very emphasis was one reason, back in 2015, that the earlier General Convention approved alternate liturgies allowing same-sex marriage but declined to alter the Book of Common Prayer. The decision sanctioned gay marriage across the American church but has allowed the bishops of eight dioceses -- Albany, Florida, Central Florida, Dallas, North Dakota, Tennessee, the Virgin Islands and Springfield., Ill. -- to opt out.

The 2018 Convention's B012 resolution, critics say, essentially weakened the authority of those eight bishops. According to the compromise, a same-sex couple can marry in their home parish -- even if the priest declines, thus requiring outside clergy or pastoral support from another diocese. (Clergy have always had a right to decline to marry people.)

"Instead of being ostracized from the home parish, it allows the wedding to happen even though the bishop and the particular priest in the parish might not agree," said Long Island Bishop Lawrence Provenzano, one of the three bishops who proposed B012. The compromise was "absolutely an effort to avoid an additional eight dioceses in the Episcopal church to contemplate leaving." As an aside, Provenzano noted his friendship with Love despite being at odds on same-sex marriage. "I think the world of him."

After three years of discussion at the national level, five bishops from the original eight dioceses ultimately approved the compromise; Love was the most adamantly and vocally opposed.

Even Love's harshest critics agree that he's consistent: From the run-up to his election as bishop in 2006 -- a position he never wanted or sought, he stresses -- he's articulated his position and the reasoning behind it. "People may disagree with him, but they can't accuse him of being fair weather or wishy-washy. He's been very clear," said William Hinrichs, who serves as a priest part-time at St. John's in Cohoes.

As bishop, Love replaced William Herzog, a conservative who opposed the 2003 consecration of V. Gene Robinson -- the now-retired head of the New Hampshire diocese who was the first bishop in an openly gay relationship. Herzog became a Catholic in 2007, though he returned to his former faith three years later.

Robinson's appointment prompted other Episcopalians to leave in the 2000s, one of several periods of change, rift and exodus in the last half-century -- sparked by, among other things, the ordination of women in the 1970s and the 1979 rewrite of the 16th-century Book of Common Prayer. (St. Thomas of Canterbury in Clifton Park, which belongs to the Anglican Church of North America, uses the original prayer book.)

The 2015 General Convention sparked another. Lanier said a contingent of "maybe 10 to 12" worshipers migrated from Albany to St. Peter's in Bennington in 2015, after Love issued a pastoral letter and delivered long and heated sermons against gay marriage. (Recalled Don Csaposs: "Oh, it was awful.") Other progressive Episcopalians migrated, and still migrate, to churches in the Central New York diocese. Conservative Episcopalians migrate here.

Despite all of this, Love said, the diocese of Albany has not yet suffered a permanent breach. It hasn't broken away or lost a parish, although a few have used something called DEPO (Delegated Episcopal Pastoral Oversight) to allow pro-gay marriage parishes to receive pastoral oversight from the bishop of Vermont while formally remaining under the purview of Albany.

He said he shepherds all of them. He said he hears those who disagree with him, even as others complain he doesn't. He reads. He prays, listening for direction. For 12 years, the bishop has asked God to correct him if he's wrong on gay marriage -- "and he hasn't," Love said. "He's only reinforced." Using the three Anglican cornerstones of discernment, he still believes that Scripture defines marriage; that tradition supports this; that reason supports it, too. God designed the male and female bodies for sexual intimacy, he said.

Poised at a juncture in a church divided, William Love feels embattled. He says that people who attack him have their own struggles, some "underlying hurt or wound or confusion, and I just happen to be the sucker that happens to be receiving the brunt of it." He says it's the Episcopal Church, ironically, that's not being inclusive when it pushes out conservative opinions.

And he can't predict what will happen on Thursday, when clergy of all viewpoints will meet from all corners of the diocese to talk, pray and discern. Resolution B012 is scheduled to go into effect on Dec. 2, the first day of Advent. What that means and how it will play out for local Episcopalians -- clergy and lay, gay and straight -- remains unknown.

"That's still to be seen. I don't know . . . . How we deal with B012 within the Diocese of Albany has not yet been determined, and that's part of my discernment process." Ultimately, Love said, "I can't control what other people do. All I hope I can do is, by God's grace, control what I do. So I don't know. At this point, my ultimate concern is not about me -- my concern is about the diocese and how best to lead and provide for the diocese. This has never been about me."

"What remains to be seen is how those bishops who are theologically opposed to same-sex marriage can honor both their theological conscience and the intention of B012," wrote Bishop Thomas Ely of Vermont in an email. "Time will tell. . . . What Bishop Love and the Diocese of Albany will do is not yet clear. My personal hope is that there are not too many barriers or hoops to jump through before couples can use these authorized liturgies locally."

Many others expressed hope. Some expressed fear of a worsening breach. Worst-case scenarios could include departing parishes (though property and finances are a complicating factor), a redrawing of the diocesan map, even a shift over to the traditionalist Anglican Church of North America.

"I'm concerned about the implementation of the resolution," said Chip Strickland, vicar at St. Paul's in Greenwich, who agrees with Love on same-sex marriage. "But I guess I'm still hopeful that we can find a way to, you know, stick it together despite our differences." Would he consider leaving? "I've been Episcopalian my whole life. I love the Episcopal church. I'm very grateful, and I owe them an awful lot -- so leaving would be an extremely difficult and painful decision, if it came to that."

Dumas, too, is a lifelong Episcopalian. But the music director doesn't picture himself getting married any longer. This whole debate has made the sacrament moot: All the talk about whether he qualifies as a gay man "has been completely desensitizing." And, frankly, has tested his faith.

Not his faith in the church. "My faith in God. My faith in God. You know, because here I am -- this is who I am -- and I'm still being called into question. Sure, the bishop says he has nothing, really, against gay people -- well, that's not true, then, is it? Because this wouldn't be an issue. You can't walk around with that double standard. . . . And so it tests me."

As for Louis Bannister, who had temporarily migrated to Bennington, he feels "very much at home" back at the Cathedral. "I think we're very good at loving each other, and supporting each other, and nurturing each other, and being there for each other. And regardless of what our issues might be outside the door, we are all extremely conscious that there be a place for everyone at the table."

By which he means the Eucharist -- the body of Christ at the altar, the literal essence of Christian worship. "And yes, I think that my devotion to Christ, as well as the bishop's, allow us to sort of bridge the chasm. But boy," he said, "it would be nice to be able to get married."

END