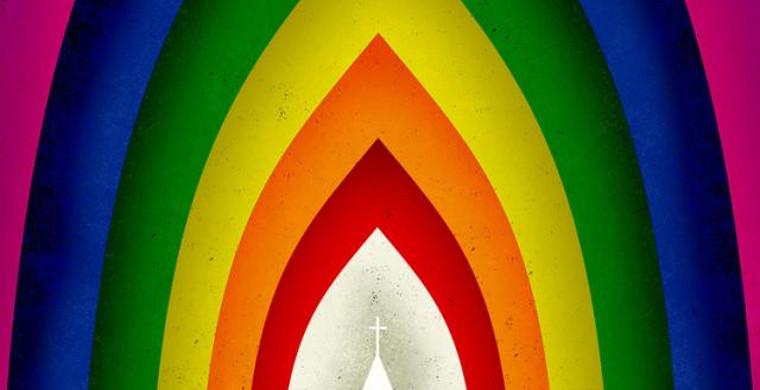

The most divisive element in American church life is no longer racism; it's homosexuality

By William B. Lawrence

DALLAS MORNING NEWS

http://www.dallasnews.com/

Nov. 22, 2016

In the past few years, Christians, including members of North Texas churches, have fought about an issue that cuts so deeply into their beliefs about God, morality and society that congregations and denominations are splintering.

The most divisive element in American church life has always been racism, from the days of slavery and segregation to Sunday morning worship attendance patterns today.

But now, American churches are facing another issue that could prove as divisive as race: homosexuality.

Christians are locked in conflicts over basic questions. Is homosexuality a moral choice or a biological identity? Can LGBTQ people be received into church membership? Can they be certified, licensed or ordained for positions of ministerial leadership in the church? Can they marry same-sex partners and have their marriages recognized by the church? If a church member professes to be attracted to people of the same sex or admits engaging in same sex practices, can she or he be removed from membership? Can gay Christians participate in the discussions of these matters, rather than simply be the objects of them? Can they do so without fear?

For people in North Texas, those are not abstract matters. Denominations that are staples of Christianity in the region are on the verge of (or in the aftermath of) schism. Congregations with links to major denominations can find no unanimity. Independent and non-denominational churches are also in the throes of separation, and many are engaged in disciplinary scandals over these same perplexing questions.

Adding to the acute nature of this is the fact that people in North Texas attend worship more regularly than most Americans. The percentage of the population that goes to church is higher in North Texas than in other regions of the country, according to the Barna Group. That amplifies the impact on society, and vice versa, where worship attendance is a major facet of the culture.

Further, in North Texas, gays go to church. And here in North Texas, churches approach homosexuality as a principle and gay Christians as people in a variety of ways. Some churches openly affirm them. Some churches include them without recognizing their same-sex partnerships or marriages. Some churches expect gay members to hide their sexual identity. Some churches offer programs to help gays live in celibacy. Some churches offer advocacy for gay rights. Some churches denounce homosexuality.

And some Christians choose to fight, either declaring they will defy their church's laws and affirm gay members or declaring that opposition to homosexuality is a non-negotiable, irreducible factor in their faith. Meanwhile, people have suffered the pain of fractured fellowship.

The largest Lutheran denomination in the country took about a decade to discern ways that it might manage to remain institutionally unified and, at the same time, accommodate intense disagreement over homosexuality. Near the end of that discernment process, one bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, who was the leader in North Texas and northern Louisiana, publicly announced he had finally accepted his identity as a gay man.

Episcopalians in North Texas have cast opposing votes in the denomination's national assembly on issues regarding homosexuality. A large parish in the Diocese of Dallas left the denomination. The Diocese of Fort Worth fractured, and some of the separated parts chose to affiliate with an Anglican diocese in South America.

United Methodists, who have prohibited the ordination and appointment of self-avowed and practicing homosexuals by church law since 1980, have elected as bishop an ordained woman who is legally married to another ordained United Methodist woman. Soon after, the South Central Jurisdictional Conference (which includes the Dallas and Fort Worth areas) asked the church's highest court to void her election.

In 2010, the largest Presbyterian denomination officially ended its ban on ordaining homosexuals. Then in 2014, the denomination ended its prohibition against clergy conducting same-sex weddings. But other "Presbyterian" denominations maintain their opposition to homosexuality. And some individual congregations have taken steps to leave the primary Presbyterian denomination, protesting against the liberalized church policy. The Presbyterians in North Texas know that such fights can split a church into three groups of people: two separate, opposing congregations and a third group so wounded by the fight that they avoid attending either church or, indeed, any church at all.

This month, after more than a year of study, prayer and discernment, Wilshire Baptist Church in Dallas (with the largest number of participating voters ever) chose to affirm "a single class of membership;" with 61 percent voting that "all members will be treated equally, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity." In the process and in the wake of the vote, some members are leaving.

Dallas' Watermark Church believes LGBTQ people may retain their membership as long as they commit to celibacy while undergoing therapy to help overcome homosexual attractions. One former member, who could not comply with those conditions, recently marked the first anniversary of Watermark's decision to expel him from membership. In a letter, church leaders had told him that his homosexuality is "a path of destruction" and that the church would treat him "as we would anyone who is living out of fellowship with God."

Churches lag society

Such divisiveness gains intensity when church life ponders its social and cultural context. Except in cases where churches prefer to separate entirely from society (the way Amish farmers or cloistered monks do), most American Christians and their church institutions engage the world. Members of churches in North Texas typically participate in business, politics, education, military service, health care and entertainment in society. Yet they work with, and tend to, people they might not welcome at worship.

When church members come from the same social strata as their economic and cultural peers, they know that whatever troubles a community troubles its congregations.

In a few cases, prophetic voices arise from the church and lead society toward major change. One example is the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, which was led by religious activists.

Yet in most cases, the voices of the churches are not a vanguard of social change but a lagging participant. It may seem odd, but churches tend to be the trailing indicators of changes in the social and cultural patterns to which they connect. For example, women were long confined to second-class status in American society, denied the right to own property and prohibited from voting, just to name two. Women's suffrage finally came early in the 20th century. But denominations like the Presbyterians and the Methodists continued to exclude women from full clergy rights for decades after that. Some churches still limit women to subordinate status.

On the topic of homosexuality, the church may be trailing the world once more. In the Obergefell vs. Hodges decision in 2015, the Supreme Court said state laws cannot prohibit marriage between people of the same sex. Many churches, however, do not honor gay marriages or permit clergy to perform them. Perhaps, decades into the future, these churches will conform to cultural change and will conduct same-sex weddings without hesitation. But for now, Christians remain divided.

The racism schism

Only one issue in American church life has caused more schism and separation than what is happening over homosexuality. That issue is racism.

And it, too, illustrates how the church might be a trailing indicator. The Supreme Court declared in its Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954 that, with regard to public schools, separate is inherently not equal. Yet it took another 14 years for the Methodist Church to end its own system that separated black and white church institutions. Racial separation is still the norm on Sundays.

Race and racism have fostered separation within America's churches and society for centuries.

For the hundreds of years of the legal slave trade that brought Africans and Afro-Caribbeans to North America, and for the hundreds of years that human beings in North America were treated as property confined in "involuntary servitude," church life tended to conform to the social and cultural norms of North America. It was a vile combination of forces -- the economic system that sustained southern agriculture, international trading partnerships that supplied slave labor, theological rationales for the inferiority of African peoples, biblical authorizations for the institution of slavery -- that allowed the American churches and the American culture to conform to a set of practices that kept races apart and confined them to an egregious imbalance of power.

Early in the 19th century, challenges to such conformity shook the church's institutions and the secular systems with which they were aligned. A social movement for the abolition of slavery became a divisive factor among Methodists, Presbyterians and Baptists in America.

In 1861, the year that Southern states seceded from the Union and that the Civil War began, the Presbyterians divided into northern and southern churches over slavery. Baptists had divided over slavery in 1845, creating the Southern Baptist Convention. In 1844, a Methodist schism over slavery created two separate Methodist denominations, one in the North and another in the South. That division lasted nearly a century.

When the Methodists decided to reunite their northern and southern factions into one denomination, race still remained divisive. In its 1939 reunion plan, The Methodist Church constructed a racially segregated system of jurisdictional conferences. It ensured that black preachers would only serve black churches and that black bishops would never supervise white churches or white ministers.

Most people celebrated the reunion of these two big Methodist bodies as a great sign that the separation had been resolved. But the joy was really a façade. What occurred among Methodists in 1939 was the replacement of one kind of schism (North/South) with another kind of separation (black/white). The price Methodism paid for settling an old schism was the cost of creating a new one.

Will fight mirror racism?

Are churches in North Texas -- and in America -- on a course toward the same sort of separation over homosexuality?

The next big denomination to come to the brink of schism over homosexuality could be The United Methodist Church. At its most recent global legislative gathering (called the General Conference), more than 100 clergy declared they are practicing homosexuals, in defiance of the church's law. After General Conference, several basic bodies in the church (called Annual Conferences) resolved to defy church laws on homosexuality regarding ordination and same-sex weddings.

Then came the election of a married lesbian as a bishop of the church.

In October, three months after her election, nearly 2,000 United Methodists met and formed a Wesleyan Covenant Association to demand that church laws regarding homosexuality be obeyed. Some of those thousands said they were ready to "lead" the denomination by insisting that church law be upheld. Others in the assembly said they were ready to "leave" the denomination in a schism that will generate a new Methodist body, whose opposition to acceptance of gays will define its identity.

United Methodist Bishops have appointed a commission to try to find a way forward from the precipice of separation. They may call a special session of the General Conference early in 2019 to hear the commission's report and decide what to do.

In North Texas, there are United Methodists on all sides of this dispute. Some want to leave the denomination rather than accept homosexuality. Some want to lead the denomination toward implementing church laws that prohibit the ordinations or marriages of gay people. Some want a Methodist church that welcomes everyone, regardless of sexual identity, into all forms of leadership and life.

This intense disagreement in America's second largest Protestant denomination may produce a landmark on the road Christians are traveling. Methodists are widely distributed across the nation. There are United Methodist churches in about 90 percent of the counties in the country, located in urban, suburban and rural areas. It is unclear whether the denomination will stay united, split in two or splinter into fragments.

There are Christians in North Texas who fuel these fights with self-righteous arrogance, but this confuses the power to write church law with the power that resides in the spirit of God to reconcile and make new. The movement of the Holy Spirit through the centuries has proved to be mightier than human systems of commerce, country and congregational order. It behooves all believers to exercise some humility before they insist -- in God's name -- on creating boundaries that divide.

America's Christians in the past divided over race, and none of us is better for it. If Christians continue toward division over homosexuality, we will leave the same legacy of bitterness that generations to come will be forced to taste.

The Rev. William B. Lawrence is professor of American church history and former dean at Southern Methodist University's Perkins School of Theology