The Neurotic Syndrome of Failed Self-Righteousness

[RELIGIOUS LEGALISM: Effects and Cure, Part II]

By Bruce Atkinson PhD

Special to Virtueonline

www.virtueonline.org

February 9, 2019

As Christian leaders, we must become better at adjusting our armor and practicing our skills with the "sword of the Spirit which is the word of God (Eph 6). For we are under attack not only from without by moral relativism and PC values in an increasingly secular culture, our churches are also being attacked from within by "wolves in sheep's clothing."

This spiritual warfare is occurring on at least two fronts-- which represent opposite ends of the spectrum of ecclesiastically sponsored evil--that is, both lawlessness and religious legalism. As indicated in Paul's letters as well as in the Lord's messages to the churches in Asia (Revelation 2-3), this is a war that has been waged for millennia. Christians and churches can be damaged and become out of balance by either too much license or too much law.

The following article was originally presented at the International Congress on Christian Counseling, in Atlanta, 1988 (I have edited it for this venue.). It was chosen by the Congress as a response to Dr. Donald Sloat's lengthy headline presentation "Healthy and Sick Religion." The essentials of Dr. Sloat's perspective can be obtained in my previous article https://www.virtueonline.org/religious-legalism-effects-and-cure-part-i .

As a clinical psychologist who worked for years in a church-related setting primarily with fellow Christians, I have seen first hand the psychological results of religious legalism. By "religious legalism" I am referring to a strong church emphasis upon obedience to strictly-defined biblical rules for right behavior and a belief that one's standing with God is dependent upon such obedience.

By over-emphasizing the "law" and human power in avoiding sin, the essential doctrines regarding God's grace and power easily lose their primary position. It may be that such a "law--works" emphasis was developed as a way to counter materialistic and hedonistic cultures. I expect that it was an attempt to increase self-control over temptation and sinful lifestyles. The legal emphasis also may be an attempt to fight the detrimental "cheap grace" universalism and other liberal theologies which do not regard moral transformation as necessary (or inevitable) with true faith.

It has been quite noticeable to me over the years that the psychospiritual consequences of cheap grace and "me-first" narcissism do not lead its victims to the counseling office as often as does malignant legalism. Those who are not guilt-ridden are psychologically OK with sinning boldly. But it has become distressingly familiar for me to see Christian clients who come from religiously legalistic backgrounds complain about the same serious symptoms of guilt, shame, and self-condemnation-- leading to depression and severe anxiety. I shall explain why this is.

It is not surprising that from family dynamics which are dominated by authoritarian control tactics and guilt manipulation (using God and the Bible as whips), we get adult Christians who view God primarily as a harsh punisher of wrong doing, a God who condemns them for not living up to certain standards of perfection, and a God who ultimately may not even forgive them. These people are sometimes highly "religious" church attending Christians. The protestant legalists are the ones who frequently doubt their salvation and may compulsively and repeatedly respond to the invitation to the unsaved during church services. The Catholic legalists will not miss a Mass for the same reasons.

What the legalistic emphasis appears to promote is either rebelliousness or perfectionism. For simplicity of understanding, I have categorized three common types of responses to growing up in a legalistic family and/or church: 1. the Prodigal Son, 2. the Pharisee, and 3. The Perfectionist.

1. The Prodigal Son. This is the antinomian rebel who sins boldly. He figures that the rules are more than he can keep, so he quits trying. He may justify his behavior with antinomianism and cheap grace theology, but generally he is just intentionally doing whatever he wants and will admit to it.

Options:

a. He repents, humbly returns and appreciates forgiveness. The greater the sin, the greater the gratefulness and love for the God who is merciful and forgives.

b. Or, he becomes comfortable in his sin, never repents, and his conscience becomes "seared" or hardened into that of a sociopath, a committed reprobate.

3. The Pharisee... Here is the self-righteous hypocrite who believes he is better than others because he keeps the rules, at least publicly. He is essentially dishonest in that he lives in denial of his heart's true distance from God. He is good at impression management and politics; he knows how to look good, but he tends to be proud, judgmental, and to have some intransigent private sins. He has 'succeeded' in convincing himself that he is righteous, but of course he is only self-righteous and farther from God than the intentional 'honest' rebel.

Options:

a. He "hits bottom" and recognizes his heart's true condition. He repents and humbly returns and appreciates forgiveness. The greater the sin, the greater the gratefulness and love for the God who forgives.

b. Or, he never relents of his proud insistence on being right with God and believing that he is better than others because he avoids the worst of sins. He becomes hateful and bitter in his elder years--and alone.

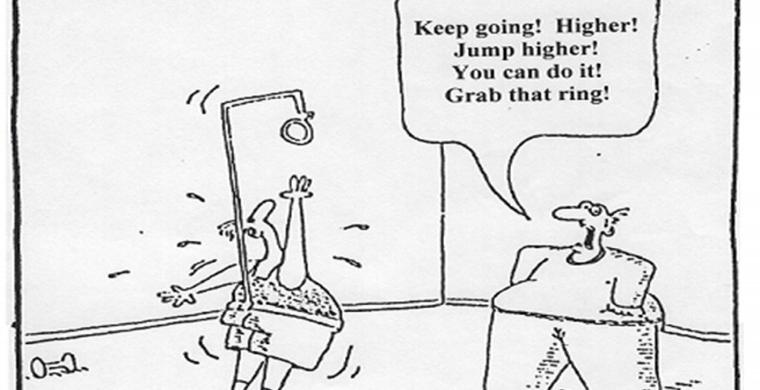

5. The Neurotic Perfectionist. This is a victim of "failed self-righteousness." He tends to be a perfectionistic but basically honest individual who is deceived into thinking he must obey every "jot and tittle" of the law in order to be saved or to be acceptable to God. For him, performance is everything. So he tries and tries and tries (he is very trying) but of course he often fails--and is devastated by it. He is subject to oppressive guilt feelings, anxiety, depression, self-condemnation, low self-esteem, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. No matter how successful he is in the world, it is never enough to cause him to feel better about himself. Since he believes that he must do it all himself and he holds himself up as judge of himself, he is unable to fully accept God's forgiveness (that is, he "plays God" and does not forgive himself).

Options:

a. He comes to understand the nature of grace and sanctification, and the fact that no one can be perfect enough by self-power. He surrenders his need to be self-righteous and gives up his need to save himself. He "lets go and lets God" fix what he cannot fix in himself. He repents of his trying to play God and accepts God's love and saving grace, trusting God completely. He allows Jesus' work on the Cross and the power of His blood to be effectual in his life. Although he continues to make human errors, his sins become less frequent and less harmful, and he has inner peace-- because he now relies on the faithfulness of His Savior rather than on his own ability to obey the rules.

b. Or, he never understands the nature of forgiveness and grace, and thereby lives increasingly in a state of despair. He may give up and commit suicide or just live in misery. Rarely, he may switch and turn into a prodigal or a hypocrite.

Some discussion is in order. I rarely see the Prodigals in my office, for they are experiencing little inner conflict and do not seek counseling. They are out in the world "sinning boldly." They will, however, have more negative consequences such as accidents, illnesses, violence, and prison.

The Pharisaical perfectionists tend to be rigid, repressed, and guarded. They experience less inner pain, at least until their highly controlled little worlds fall apart. These tightly-defended perfectionists are in less distress because they have convinced themselves that they have covered all their bases, that they have obeyed the rules, that they have earned their salvation. These I call the "successfully self-righteous" ones, and they are much like the Pharisees of Jesus' day. Their religious pride has blinded them to the reality of their own inadequacy and deep need of healing and change. They tend to be addicted to looking down on others as a way of building up their own egos. They are Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde types, with extreme care being taken to present an unassailable public image, but when "safe" at home, their families often see another side: a person who is highly critical, judgmental, demanding, controlling, and often abusive.

However, the Failed Self-righteous are more honest and open than the Pharisees. They cannot hide their failures from themselves, so they are constantly conflicted and hurting. These are the people I see frequently. They are frustrated and guilt-ridden. Of course their attempts to reach perfection or holiness always fall short. But unlike the other victims of legalism, it really, really bothers them. What they are really striving to achieve (without realizing it) is the outward appearance of righteousness rather than the true God-given righteousness of Christ.They want to take credit for their righteousness, but God blesses them by making sure that they fail in their striving. Their striving only results in strife. This is why I call this symptom pattern "the neurotic syndrome of failed self-righteousness." "Neurotic" here is in reference to their lack of awareness; that is, they live in unconscious denial that they are actually powerless to make themselves righteous or to make other people happy.

These often well-intentioned individuals are prone to have very low self-esteem which tends to lead to passivity, avoidance, easily giving up, poor insight, and inhibited emotional expression. They are taught by their legalistic peers to hide their feelings of inadequacy and to put on a hyper-moral front. There is often a long-term dysthymic (depressive) lifestyle. Chronic self-condemnation and the fear of both punishment and rejection tend to lead to chronic anxiety and guilt feelings. It is no wonder they have impoverished relationships associated with a fear of openness and intimacy. Another common difficulty is over-responsibility; all the problems of their families are theirs, the burdens of the world are theirs to fix. Codependent caretaking is common.

According to psychiatric diagnostic terminology, the victims of religious legalism can evidence the whole range of anxiety and mood disorders (especially neurotic depression), with a sprinkling of somatoform and psychosexual disorders. Obsessive-compulsive traits are commonplace, as are traits associated avoidant, dependent, histrionic, and passive-aggressive personalities.

I return briefly to a basic cause of their difficulties: perfectionism. Dr. Aaron Beck was an example of one of the multitude of mental health professionals who researched and treated depression, and who pointed to perfectionism as a causal factor. Because none of us behave perfectly at all times, especially according to common Judeo-Christian standards, an attitude of perfectionism can condemn Christians to continual frustration, self-rejection, and consequently, to great difficulty believing in God's forgiveness and acceptance.

Christian perfectionists may believe at an intellectual level that they are forgiven by God, but because they do not forgive themselves, they don't allow themselves to fully receive the benefits of God's forgiveness. They tend to "play God" in this one area-- their pronounced self-judgment is more meaningful to them than God's forgiveness. They cannot fathom how a sovereign, just, and holy God could possibly forgive and accept them. So it is my hypothesis that Christ's work on the cross has not been fully received by these people at the emotional level. They somehow feel that they must be worthy. Of course, we know that no one is worthy, that "the ground is level at the foot of the cross." No one truly deserves it. We receive forgiveness and salvation as a free gift or not at all.

I distinguish between two ways of viewing perfection. The healthy view regards perfection as a desired goal of completion or maturity, a goal that we cannot fully achieve in this life. Rather than a place or state of being in this life, full sanctification should be regarded as a process. Like "true north" on a compass, the ideal of perfection is meant to show us the direction which we expect to be moving, which we expect God to be moving us as we mature in the faith. My advice: Seek to move toward the perfection of Christ ("be ye perfect..."), but don't beat yourself up because you are not there yet. No one is.

So, there is indeed a negative side to the pursuit of perfection or holiness. This endeavor becomes pathogenic when it is regarded as a state which we "should" have already reached, or when it becomes a goal which is solely our responsibility to achieve. This is because, as human beings, we don't have the power to perfectly adhere to all the subtle standards revealed in the Bible. Who can love everyone perfectly all of the time except God Himself? Since we don't hold the power in and of ourselves to love perfectly, then the responsibility cannot be ours either. People are only responsible for what they can actually accomplish, not for what is beyond their ability.

So what are our true responsibilities? As the New Testament emphasizes, our responsibility consists mainly in believing and trusting God to use His power to get us where we need to be. We were not created like robots; God will not force us to become better people without our permission. Therefore, it is our first responsibility to give God that permission, to say "Yes!" to God, to commit ourselves and all aspects of our lives into His gracious hands.

Secondly, our responsibility is to trust Him to take care of us, being "anxious for nothing." We are to trust His love, grace, wisdom, and power in the process of our spiritual growth (sanctification). As Philippians 2:13 makes clear, it is GOD who "works in us both to will and do of His good pleasure." If we rely upon ourselves, we are in big trouble. The more we rely upon ourselves to perfectly obey, the more we get in God's way.

Christians suffering with perfectionism need to be reminded that we are not our own; we were "bought with a price", and this fact is very, very beneficial. If we were our own, we would be lost. Fortunately, as the "author and finisher of our faith", the credit for our completion will always belong to Christ.

These biblical principles need to be taught more widely, especially among our more fundamentalist brothers and sisters. For Christian counselors, such truths can encourage our perfectionistic clients and begin to destroy the deceptive cognitive virus that is legalism and minimize its negative consequences.

Although I agree with Dr. Sloat in his major thesis, as indicated above, I DO have a criticism. In his books, the good doctor attacks the word "holiness" as applied to believers and wishes it were stricken from our language. However, I think it is an excellent biblical term. It is only the legalistic misunderstanding of holiness which twists it into a pejorative thing. Instead of the conclusion that holiness is a bad thing therefore should be replaced by "wholeness", why not simply make it clear: what the legalists strive for is NOT holiness at all but self-righteousness!

Holiness IS the good thing to be desired. But holiness is not obtained by works or striving; like our salvation, we cannot earn it. Holiness is obtained by the free grace of God, through our faith. God Himself changes our hearts, providing an innermost desire to be close to Him and to be used for His divine purposes. It is the heart, our inner being, that God is primarily concerned with.

Of course, we would expect to see good works flowing from a person who stays close to God, but the works themselves do not make anyone holy. Holiness is an inner quality (like spiritual fruit in John 15 and Galatians 5:22-25) which only God can produce in us as we abide in Christ. God does so by choosing us and equipping us for His purposes; and only God is truly qualified to judge where each individual currently is on that road to perfection.

"If the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed," (John 8:36)

Dr. Atkinson is a graduate of Fuller Theological Seminary with a doctorate in clinical psychology and an M.A. in theology. He is a "cradle Episcopalian" who left TEC in 2004. He is a founding member of Trinity Anglican Church (ACNA) in Douglasville, Georgia.