Paradoxes in Passion Week

By John G. Stackhouse

https://www.thinkbettermedia.ca/

March 26, 2024

Thomas Cranmer's prayer (in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer) for Palm Sunday, just past, contains not just one, but two, paradoxes.

Almighty and everliving God, in your tender love for the human race you sent your Son our Saviour Jesus Christ to take upon him our nature, and to suffer death upon the cross, giving us the example of his great humility: Mercifully grant that we may walk in the way of his suffering, and also share in his resurrection; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, forever and ever. Amen.

Cranmer clearly has before him—perhaps literally open to the page—Philippians 2:5-11:

Let the same mind be in you that was even in Christ Jesus,

Who being in the form of God, thought it no robbery to be equal with God:

But he made himself of no reputation, and took on him the form of a servant, and was made like unto men, and was found in shape as a man.

He humbled himself, and became obedient unto the death, even the death of the cross.

Wherefore God hath also highly exalted him, and given him a name above every name.

That at the Name of Jesus should every knee bow, both of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth.

And that every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is the Lord, unto the glory of God the Father.

(I don't have the text from the Great Bible at hand, so the Geneva Bible can substitute here.)

The first paradox I notice is Cranmer's ascribing to Jesus "great humility." "Great" seems an odd modified for "humility," doesn't it?

Yet, as I have been learning from Prof. Eve-Marie Becker's fine study of Paul on Humility, when one construes humility as Paul does, it could indeed be called "great." Paul sees humility as a choice, as a posture one deliberately assumes in order to benefit the Church, preferring the interests of one's fellows to one's own.

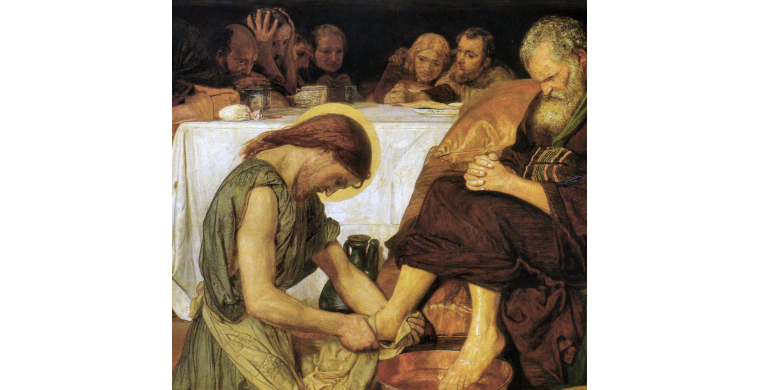

Understood that way, Christ's humility is great indeed. He who enjoyed the very form of God condescended to take instead the form of a slave, to serve the Church to the uttermost—"even the death of the cross."

The Son of God thus traversed the greatest of social distances: from the highest to the lowest. He made the greatest of exchanges: from the bliss of heaven to the agony of atonement. He underwent the greatest of status changes: from the Lord adored by heavenly beings to the Crucified mocked by his own people and abandoned by his own friends.

He thus indeed sets us The Example, as Paul says: "let the same mind be in you that was even in Christ Jesus."

Nietzsche is dumbfounded by this transvaluation of values—until he explodes in eloquent rage against it. Worship a victim? Venerate a loser? Adore a slave? Christianity is lunacy—

—or it is the greatest story ever told, as God lifts up the poor in spirit and hauls down the pompous to vindicate righteousness and destroy oppression. And we therefore should be busy in the abject and enthusiastic service of that Supreme Slave, our Lord and Saviour, who models for us truly great humility.

So we come to Cranmer's second paradox, his prayer that God will "mercifully grant that we may walk in the way of his suffering."

Just a moment, please, Archbishop. That would not be my first choice of prayers to God's mercy.

My first choice would be, "Please don't hold my many sins against me." My second choice would be, "Please don't give up on me in my half-hearted attempt to walk in your Way." The third choice would be, "Please give me a more pleasant life than I deserve."

A long way down the list of prayers I might pray to God's mercy would be, "Please give me a life of suffering like Jesus' life was." Yet this is Cranmer's prayer, as it is the implication of Paul's inspired teaching.

Walking in the way of Jesus' suffering is the only way to follow Jesus. Jesus' way was the way of suffering, and he prophesied that all who followed him would have to take up a cross and walk a similar path (Matthew 16:34). Persecution comes as a matter of course. The world resisted Jesus; the world will resist Jesus people (John 15:20).

Christianity doesn't valorize suffering. Suffering isn't good in itself. One day all suffering will cease in God's new era.

In this era, however, suffering is the way, the only way, to get certain things done. Christian things. Christ-like things.

Like campaigning for justice. Like protecting the vulnerable. Like emancipating victims. Like sharing the gospel. Like building healthy families and churches and other institutions.

So if we are truly seeking the Kingdom of God and his righteousness, we are wanting the way of Christ, which is the way of suffering.

And as Cranmer says—echoing Paul and his Lord before him—suffering in Jesus' way is how we eventually arrive at the destination Christ has put at the end of that way: resurrection. A life properly spent is a life blessed with reward.

May God therefore kindly, graciously, mercifully grant us what we do not deserve: the great dignity of following his own Son on his royal way. May God mercifully grant us what we cannot choose in our own pathetic moral weakness: the great humility of following his own Son on his way to the Cross.

And may God mercifully grant us the most gloriously disproportionate outcome to our small strivings: resurrection into the unimaginable beauty of the world to come, where all suffering will cease and joy will reign.

My friend, may the way of Jesus be plain before you this Passion Week. May you be granted the strength to walk in it. And may you faithfully greet the dawn of Easter. Please pray the same for me.

END